Compared to other Latin American countries, Cuba has always been a little different; they were one of the last two countries to declare independence and abolish slavery. They also had a tumultuous relationship with the United States for the past 60 years; while other Latin American countries’ relationships were often sour, Cuba’s was especially bad. From their time as a colonial sugar and tobacco producing powerhouse to their current state, Cuban society and national identity have changed. But what caused this change? Fidel Castro’s revolution played the main role in changing Cuban life, but the US had its place in this change as well. Their foreign policy in Latin America aided this shift in Cuban identity and their actions during the Cold War amplified it further.

The United States in Latin America

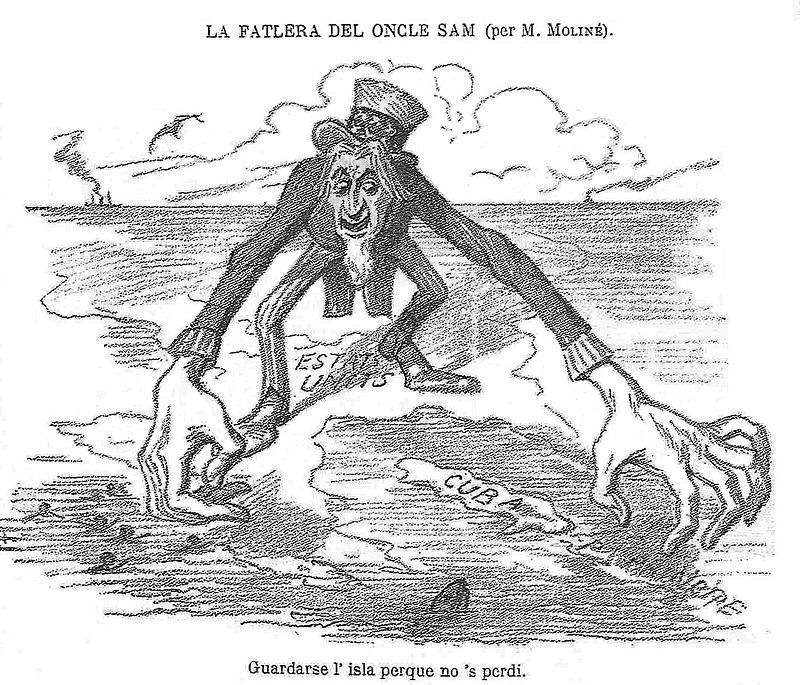

To analyze the change in Cuban identity, we need to examine how the US acted in Latin America in the early 1900s. The Monroe Doctrine, the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, and the Platt Amendment gave the US unopposed access to Latin America as a whole. They were involved almost every facet of their political and economic spheres, making sure that whatever Latin America was doing was in the US’s interest (Chasteen 2016). In the first half of the twentieth century, socialist ideas spread throughout Latin America like wildfire which alarmed the US, who felt those ideas would directly undermine their involvement in Latin America and made stopping it their number one priority. Socialism continued to grow and to combat it the US installed pro-US dictators through in areas they identified would be hotspots for the growth of socialist ideas. They could not allow communism to gain a foothold in Latin America so they thought it would be easier to put a dictator that supported the US in power rather than slowly build a democracy that could become a victim to socialism (Chasteen 2016). The political cartoon “La Fatlera del Oncle Sam” shows the US mindset in Latin America, depicting Uncle Sam as a villainous character attempting to seize Cuba for the US’s control. As this happened in more and more countries, the disapproval of American intervention began to grow.

Cuba fell victim to this trend. In the twenty years preceding the Cuban Revolution, the island was ruled by Fulgencio Batista, a dictator whose regime was backed by the US (Dunne 2011, 449). Batista’s regime became awfully corrupt and brutal, and had strong ties to organized crime. Despite this, the US had widespread investments in Cuba and stopping the spread of communism through the region was their number one priority, so they continued to support Batista in opposition to Castro’s popular movement (Dunne 2011, 449). By the end of the 1950’s, Castro’s supporters were fed up with Batista’s rule and decided it would go on no longer. Fidel Castro, a socialist revolutionary, led the working class in overthrowing Batista’s government and was named the Prime Minister of Cuba. He promised to deliver policies that put Cubans first and strongly opposed US influence. Already, the US’s policies are starting to influence changes in Cuban society.

Social Changes After the Revolution

Once Castro took power, he completely changed the way Cuba functioned as a civilization. The island no longer served the US’s capitalist interests, instead, Cubans were the focus. Castro enacted laws that massively altered how five aspects of Cuban life were lived: the mass media, the armed forces, the mass organization of labor, the school system, and the Party (Fagen 1966, 257). Together, these laws and institutions formed what Castro called “The New Cuban Man”, and though these changes were controlled by the state to teach their citizens to view the world in a certain way, it marked a significant turning point in Cuban identity. Castro’s control of the mass media gave him wide outreach to Cubans. He controlled multiple newspapers and often gave long “marathon” speeches on TV where he would rally, motivate, and mobilize his populace with Cuban nationalism (Fagen 1966, 258). The newly utilized mass media created a sense of Cubans being proud of their country and free of the United States’ control.

Fidel Castro came to power with the help of the Rebel Army, so to honor this in his new policies, the national militia was created to maintain the important symbolism of the armed forces. Fagen (1966) explains the establishment of the militia brought popular support for the regime and within a year had over 200,000 men and women in service, however, the militia ran much deeper than just those in service (259). In accordance with the new policies, professional associations were organized into support units to aid the militia and subsequently each occupational association was considered to be an essential branch of the militia (Fagen 1966, 259). This involvement brought forth great pride for Castro’s regime as well as the Revolution which became a cornerstone of Cuban culture. It gave the men and women who had not fought in the revolution itself the ability to feel as if they were a part of it which further developed the sense of Cuban national pride.

Mirroring the integration of professional associations into the national militia, one of the main characteristics of Castro’s new government was the mass organization of Cubans. A vast array of other professions and citizens, such as teachers, farmers, students, the youth, and women, were organized into federations to aid Castro’ regime (Fagen 1966, 260). Their duty was to accomplish “revolutionary tasks”, which included communication, coordination, control, and education with the aim of having ordinary citizens understand the importance of Revolution and their own place in the transformation of their country (Fagen 1966, 260). The Comites de Defensa de la Revolucion (Committees for the Defense of the Revolution or CDR) was also established to suppress grassroots rebellion movements, which roughly 20% of the Cuban population was involved with (Fagen 1966, 260). Castro’s mass organization of the Cuban population allowed him to gather his people under the revolutionary banner and instilled the idea that the jobs they did were beneficial for the regime. By bringing the people together under this program he was able to effectively unite the Cuban population under the new Cuban identity.

The education system was also altered by Castro and was a vital instrument in shaping the Cuban youth’s world view. Castro believed the most important education is the political education of the people which led him to put a large emphasis on the importance of schools and their curriculum (Fagen 1966, 261). Naturally, the schools he established taught his Marxist-Leninist political ideology which helped him align the Cubans’ views with his own. Three Escuelas de Instruccion Revolucionaria, or Schools for Revolutionary Instruction, were established: National, Provincial, and Basic offering eighteen, nine, and five month courses respectively; about 85% of the graduates of the system came from the Basic Schools (Fagen 1966, 262). The new education system also worked to eliminate illiteracy across the island while uniting Cubans’ though a common ideology. Regardless of the level of theoretical freedom the Cubans had, they were brought together by ideologies in the new schooling system.

The final aspect of the policies enacted by Castro was the establishment of the Pardito Comunista de Cuba, or Communist Party of Cuba, commonly shortened to The Party. Castro ruled under The Party for during his time in office, which he used to advance the aforementioned goals of mass organization, communication, coordination, control, and education of the Cuban people. It served as the final step in the pursuit of unanimity and the total utilization of human resources (Fagen 1966, 263). Their victory in the revolution was used to prop up The Party and was a symbol that Cubans could find pride in. As a whole, The Party coordinated all of the facets of Cuban life to which they provided unity and coherence. Though Cubans were under strict control and guidance of The Party, they were instrumental in the creation of “The New Cuban Man”, cementing the first steps of the changing the Cuban national identity in response to prior US foreign policy.

The United States’ Foreign Policy Post-Cuban Revolution and the Implications of the Cold War

It was at this point that the US and Cuba were officially enemies. In the US’s eyes, Cuba’s transformation into a socialist state had betrayed their interests, which made them very bitter. As the latter half of the twentieth century was underway, the US began to pursue increasingly aggressive foreign policy in spite of Cuba and aimed to regain political and economic influence on the island. The CIA was responsible for a large part of what happened in Cuba. They were extremely active in Latin America as the US continued to pursue their interests and often stretched the boundaries of what actions were considered acceptable to do. Castro’s political clout allowed him to use these actions against Cuba, both diplomatic and physical, to gather support from Cubans (Leo Grande 2015, 956). The intensification of foreign policy amplified the Cubans’ already negative feelings towards the US and was a key factor in developing the new Cuban identity.

Perhaps the most infamous example of aggressive US foreign policy is the Bay of Pigs. The operation was designed by the US’s government to have a small armed force land on Cuba with the goal of assassinating Fidel Castro, but unfortunately for the US, it failed and Castro survived. This type of operation was common throughout Latin America, and even the world, at the time as the US tried to assassinate leaders of countries who didn’t comply with their beliefs or overthrow them by supporting local coups (Chasteen 2016). The sense of nationalism in Cuba had been rising since Castro introduced the policies to create “The New Cuban Man” and the Bay of Pigs amplified it (Dunne 2011, 453). Consequently for the US, the failure of blatantly attempting to assassinate their leader caused rapid anti-American sentiment and support for Castro in Cuba to rise simultaneously (Dunne 2011, 456). This is one example of aggression employed by the US in Cuban affairs during the Cold War helping change the Cuban identity.

Another example of the CIA’s greatest overreaches was the destruction of a Cuban plane carrying Cuban civilians, among other nationalities, which Castro vividly discussed in a speech he delivered in 1976. After initially being skeptical of the CIA being responsible for the attack, Castro later confirmed that it was carried out by two undercover CIA agents, Hernan Ricardo and Felix Martinez Suarez who posed as Venezuelans (Castro 1976, 12). He denounced the aggressions carried out by the US against Cuba and the world, and encouraged people to recognize that the CIA had been the author of criminal actions that had increasingly been affecting the international community (Castro 1976, 14-15). He explained that those terrorist attacks were a part of the hostile policies that were unleashed on Cuba by the United States and went on to say they could not stop the revolution or intimidate the Cuban people because the Cubans had become much closer to one another through the attacks (16). We can see first-hand from Castro that the US’s foreign policy has helped form the new Cuban identity because their over aggression towards Cuba caused Cuban patriotism and nationalism to grow stronger. Castro also used words like under “siege” and “imperialists”, in regard to the US operations in South Korea and Africa, “Homeland” to gather feelings for Cuba in response to American attacks, and “sinister Yankee organization” in reference to the CIA. The actions committed by the CIA against Cuban citizens combined with Castro’s public speaking prowess worked together to promote Cuban pride and advance the Cuban identity Castro had been forming over his time in office.

The final example of aggressive US policy towards Cuba are the economic sanctions that lasted for 40 years. In 1960, the United States’ expanded the embargo on the sale of firearms to Cuba to include all goods except food and medicine, which were then included in the sanction two years later. The sanctions’ strictness fluctuated depending on who was the United States’ president at the time, but when looking at Cuban identity, the implications of the embargo are more important than the specific terms. They were enacted with the primary goal of forcing Castro’s regime out of power or manipulating it to the United States government’s will LeoGrande 2015, 939); but once the US government realized that the sanctions would not work to achieve this, their focus shifted to directly punishing Cuba (LeoGrande 2015, 944).

The embargo worked at first due to Cuba’s capital stock being made up of United States machines, but luckily for Cubans, the Soviet Union filled the United States’ shoes as Cuba’s largest trading partner, tying them even closer to communism which the United States hated. As trade with the US fell to 0% for Cuba, trade with the Soviet Union hiked up to 49%, and because of this, the embargo ended up being more of an annoyance to Cubans than an actual threat (LeoGrande 2015, 953). Anti-American sentiment became even more prominent during these times which was exacerbated by the tight cooperation with the Soviet Union, the United States’ main enemy. As a whole, the unilateral sanctions only proved to be successful during periods of world economic decline; the rest of the time Cuba still had access to other countries’ economies. The sanctions primarily hurt the most vulnerable socioeconomic groups in Cuba due to the prohibiting the sale of US medicine, which harshly impacted the Cuban health care system (LeoGrande 2015, 953-954). The implications of the United States’ embargo on Cuba, as well as Fidel Castro’s response to it, were vital in shifting Cuban identity and increasing pro-Cuban nationalist feelings with the help of anti-American sentiment.

Conclusion

The United States’ policy in Latin America during the late 1800s and early 1900s was a main factor in the formation of a new Cuban identity and the aggressiveness pursued by the United States and CIA during the Cold War amplified it. The United States failed to accept that Cuban popular opinion strongly favored Castro, or at least his ideas, and the CIA’s ignorance caused the United States’ blindness in their pursuit of foreign policy. As a whole, their lust for international economic and political influence led to a deteriorating relationship with Cuba and its people and allowed Castro to implement policies to rid the island of US influence and put Cubans first. Continued struggles with Washington proved to be a vital weapon for Castro due to his effectiveness of mobilizing domestic support from these conflicts and Cuban pride only grew stronger and stronger as their backs were against the walls.

Works Cited

Castro, Fidel. “Fidel Castro Denounces Aggressions Against Cuba.” The Black Scholar 8, no. 3 (1976): 10-17.

Chasteen, John C. 2016. Born in Blood and Fire.4thed. New York: W.W. Norton.

Dunne, Michael. “Perfect Failure: The USA, Cuba and they Bay of Pigs, 1961.” The Political Quarterly 82, no. 3 (2011): 448-458.

Fagen, Richard R. “Mass Mobilization in Cuba: The Symbolism of Struggle.” Journal of International Affairs 20, no. 2 (1966): 254-271.

LeoGrande, William M. “A Policy Long Past Its Expiration Date: US Economic Sanctions Against Cuba.” Social Research: An International Quarterly 82, no. 4 (2015): 939-966.

Moline, Manuel. 1896. “La Fatlera Del Oncle Sam.”

Stretton, Richard. 2017. “Flight 455 and the Cuban DC-8s.” https://www.yesterdaysairlines.com/airline-history-blog/flight-455-the-cuban-dc-8s