Introduction

Beginning in 1492, conquistadors from the Iberian peninsula arrived in Latin America. They encountered the indigenous peoples who had been living on the land for centuries and deemed them barbaric and uncivilized and themselves as superior and god-like. They then colonized the region, forcing all to convert to Catholicism, taking control of the land and generally exploiting the people and the region. The Spanish and Portuguese forced indigenous peoples to acculturate to their own beliefs, they taught them Spanish, implemented the laws that were present in Spain and made Catholicism the ultimate belief system. Overtime, they passed laws creating a social hierarchy to maintain power known as the Casta System. This system ensured European superiority in all sections of life. They remained in control of the region until the 1820s, when countries began to fight and gain their independence. Despite gaining independence and no longer being under colonial rule, a social hierarchy remained in place leaving those of indigenous and African descent on the bottom. The Casta System was created in colonial times to explain mixed race families to those back in Spain but this racial hierarchy remained in place long after the Spanish had left Latin America. The Casta System was created by the Spanish to maintain their power and superiority to other racial groups in the colonies. This system was used throughout their rule and continued to be unofficially in place after independence.

Casta Paintings

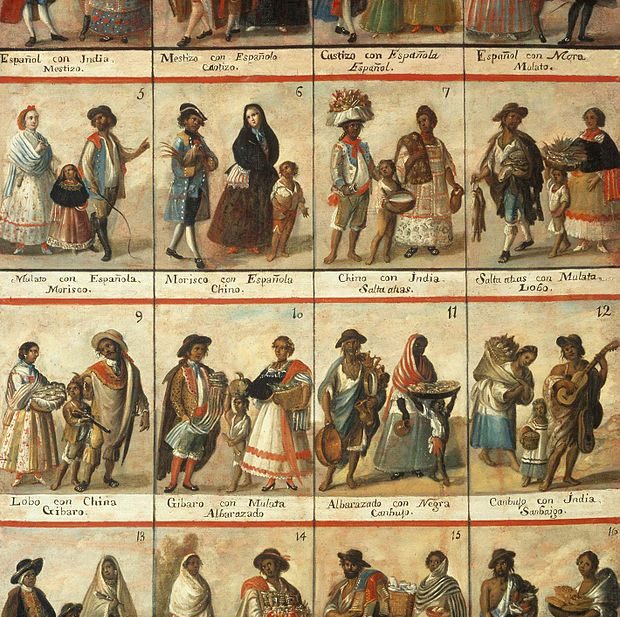

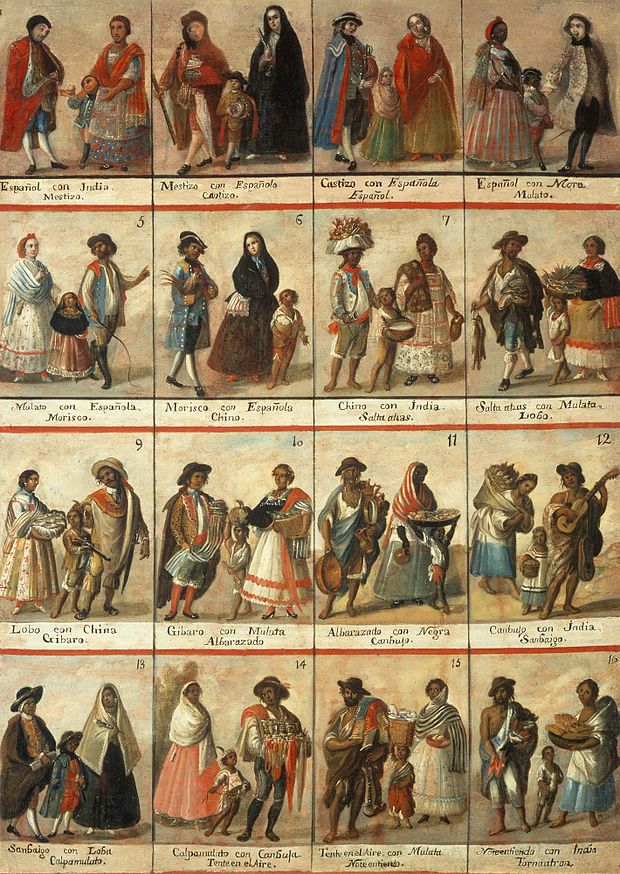

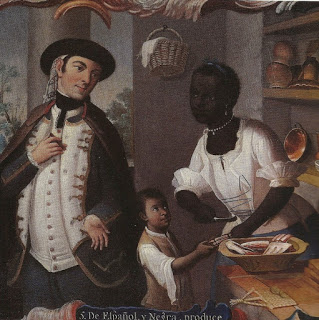

Casta Paintings were a series of paintings created in the late 1700s. They were painted for the general public of Spain to show them the racial diversity and mixing of the people in the “New World”. There are individual paintings as well as a large painting by Ignacio María Barreda that has panels showing all the different “types of mixing” in one work. There were twenty-two classifications depicted (Bustamante) and under each panel there is an inscription with the “official name” of each racial group. Each panel represents a family, a mother, father and child all together in a domestic settings the position of the panel also indicates their position in society is based on what it is in the paintings, and thus unmovable or unchangeable. (Guzauskyte, 175). The paintings show mixtures of 3 main races: Spanish (White), Native and African (Guzauskyte, 175) .The background objects are almost as important as the people themselves as they represent the status of this particular race. Couples that have a Spanish or white mother or father tend to show the highest status of wealth with very nice clothes, nice domestic objects surrounding them and in some paintings a sign of education through a chalkboard or books. Other couples, particularly those with people of African descent are shown in a simpler setting and at times demonstrating racist troupes. In one painting with a white husband and African woman, the woman is portrayed as violent and the man as innocent. These paintings show the different racial mixtures in Latin America but the objects used in the paintings are what truly should be focused on as they tell us the status of each group according to the artist (Liebsohn and Mundy).

Due to lack of technology and access, those still living in Spain did not always understand the functions of the new world and considering that most of the inhabitants in the country were white it was probably harder to envision racial mixing. The Casta paintings were then commissioned to explain the multi-racial society in Latin America to elites in Spain. The paintings illustrate the racial mixing and give examples of the positive and negative implications of mixed race families (Liebsohn and Mundy). The positives and negatives can be seen through the clothing, objects and positions of the people in the paintings with some shown has happy and healthy relationships with wealth, prosperity and education and others detail a life of violence and misery in a poor setting. Indigenous people portrayed in the paintings are described as “barbaric” and compromised of 2 indigenous peoples implying that they are too uncivilized to mix with. The paintings were also “Used by enlightened thinkers to find order and rational explanations for both the natural and social world.” (Liebsohn and Mundy).

The Legal and Societal Implications

The paintings were only one part of the Casta System, they created a visual basis for them but there were also legal actions being taken to ensure superiority. Adrian Masters in his work, “A thousand invisible architects: vassals, the petition and response system, and the creation of Spanish imperial caste legislation”, discusses some of the legal action that was taken by the Spanish to ensure superiority. There were laws created restricting certain races from being in certain occupations. A Spanish Friar approached Spanish law makers and stated that Mestizos, who were a combination of Spanish and Indigenous parentage should not be allowed to become priests in 1578, this was eventually amended to allow them to become priests however the church was very cautious and there was very little opportunity for mestizos to advance to a higher position (Masters. Many of these laws were created in Spain, thousands of miles away from Latin America and with no consultation with those impacted. Additionally, the crown used the words, Indian, cannibal and cacique when referring to indigenous peoples in legal matters which just furthered negative stereotypes and made it seem that they were not fit to be in higher positions in society (Masters).

The paintings highlight twenty two different racial combinations and provide different names for each to classify them (Bustamante). Liebsohn and Mundy however have found that communities may not have had as strict record keeping as they thought. When looking at records from Parishes, they found that they mainly used five terms: Spanish, Indian, mulatto and mestizo and members of these groups could go between them at times (Liebsohn and Mundy).This shows that though this multitude of groups existed it was a bit too complicated for record keeping to be using twenty two different categories instead settling for only five which gives only a general over view of the types of families present in Latin America. In his work The Matter was Never Resolved”: The “Casta” System in Colonial New Mexico, 1693-1823.”, Bustamante calls into question the success of the system in separating racial groups and creating a hierarchy. He believes that it was a lot more complicated to instill order in certain areas mainly due to acculturation. As previously stated, when the Spanish invaded Latin America and took control, they imposed some strict rules on indigenous peoples which lead to acculturation. People in Latin America were forced to speak Spanish, convert to Catholicism and adopt Spanish social practices. These changes made it more difficult than to emphasize differences when they had just stressed uniformity in terms of culture (Bustamante). The general conclusion made by Bustamante was that the Casta System was more successfully installed in some areas than in others.

There were other issues as well with the Casta System that called into question its effectiveness. In the book Purchasing Whiteness: Pardos, Mulattos, and the Quest for Social Mobility in the Spanish Indies, Ann Twinam discusses the ways in which the system was flexible and how people could move within it. She specifically discusses the decree “Gracias al sacar” which would allow people to purchase whiteness in exchange for a higher social standing. This allowed people of other racial groups who were wealthy enough to gain a higher social standing despite being mixed race or another race. It is an interesting caveat for this “social hierarchy” that previously seemed to be set in stone however there were not many cases of people purchasing a higher social standing. The program was not very well publicized so few people were aware it was an option. This looks to be a way to prevent social movement while also making it seem like it is an option and the playing field is more equal than it is. In addition to this, those who did attain a higher social status because of the decree often did not speak out against the system. This meant they left behind those in their own social class furthering the power of the Casta system (Twinam).

Social Structure Post Independence

In the early 1800s, those living in the colonies, especially those at the top of the social hierarchy began to grow tired of the controlling government making laws all the way in Spain. They wanted more autonomy and control over their own regions and by the early 1820s, most countries were independent and able to create their own government and social systems (Chasteen). The movements were mainly led by creoles or people of Spanish descent who were born in Latin America, placing them at the second most powerful position of the hierarchy behind those of Spanish descent who were born in Spain. These leaders did not want to be a lower rank just because of where they were born so they began to push for independence. They sold others in their nations on a new social hierarchy different from the one the Spanish imposed, giving more rights to those who were lower in the social system which helped them gain more support for their movements.

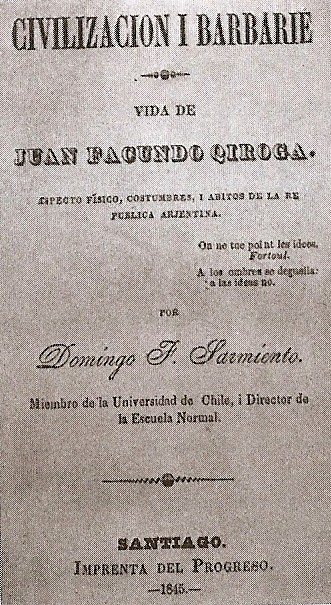

Once the Wars of Independence were over and the countries were free from the Spanish, who had installed the Casta System there was an assumption that racial classes would gain equal rights. However, this was not the case, slavery was not abolished in many countries until years later and most of the main actors in the Revolution and the subsequent governments were of European descent but born in Latin America (creoles). In an excerpt from an essay written by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento in 1845, we can see that the Casta system and negative stereotypes about other races remained in place after independence. At the time Sarmiento was living in exile in Chile but he would late become the Liberal President of Argentina. He starts by stating that Argentina is a very large country made up of many different areas, mainly referring to rural and urban areas. When discussing these areas, he looks at the dichotomy of country men and city men. The country man is more likely to stay in their local area, not having any interest in venturing to the city or anywhere else in the country. The city man is described as very well dressed and “civilized”. Sarmiento especially emphasizes the “European” qualities of the city man. This equates civilized with European illustrating that even without direct Spanish influence, people of European descent were still seen as the most important and aspirational. Race though not explicitly mentioned is still seen through the emphasis Sarmiento places on European influence and his desire for more people from Europe to immigrate to Argentina.

Conclusion

The Casta System had long and complex implications on Latin American society, some of which may still exist today. Though this system was introduced by the Spanish it continued to be facilitated and encouraged by those in the higher classes of society to ensure power did not fall into the wrong hands. The Casta System created an image and idea of racial mixes in Latin America and enforced the stereotypes that went along with certain races. Race is a complex issue in Latin America and there are still many inequalities present when it comes to different racial groups, with some indigenous peoples still trying to fight for more rights. The Casta system began as a way to ensure power for Europeans by creating a false sense of superiority for themselves and placing those who were not European at the bottom of the hierarchy.

Works Cited

Bustamante, Adrian. 1991. “The Matter was Never Resolved”: The “Casta” System in Colonial New Mexico, 1693-1823.” New Mexico Historical Review 66 (2) (Apr 01): 143.

“Casta.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, March 17, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Casta.

“Casta Painting ALL.” Wikipedia, August 27, 2011. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Casta_painting_all.jpg

De Español y Negra, Mulata. C. late seventeenth century. Oil on copper. 36 cm x 48 cm. Museo de América, Madrid. Artstor. Accessed November 28, 2016.

“Facundo.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, March 30, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Facundo.

Guzauskyte, Evelina. 2009. “Fragmented Borders, Fallen Men, Bestial Women: Violence in the Casta Paintings of Eighteenth-Century New Spain.” Bulletin of Spanish Studies 86 (2): 175-204.

Leibsohn, Dana and Barbara E. Mundy. Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520-1820. http://www.fordham.edu/vistas, 2015.

Masters, Adrian. “A thousand invisible architects: vassals, the petition and response system, and the creation of Spanish imperial caste legislation.” Hispanic American Historical Review 98, no. 3 (2018): 377-406.

O’Neal, Eugenia. “Race and Identity in the Casta Paintings of New Spain.” Race and Identity in the Casta Paintings of New Spain. Blogger, July 14, 2019. https://caribbeanpast.blogspot.com/2019/04/castapaintings.html.

Sarmiento, Domingo Faustino. 1845. “Civilization versus Barbarism” in Problems in Modern Latin America, edited by James A. Wood and Anna Rose Alexander. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield.

Twinam, Ann, 1946. 2015. Purchasing Whiteness: Pardos, Mulattos, and the Quest for Social Mobility in the Spanish Indies. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.