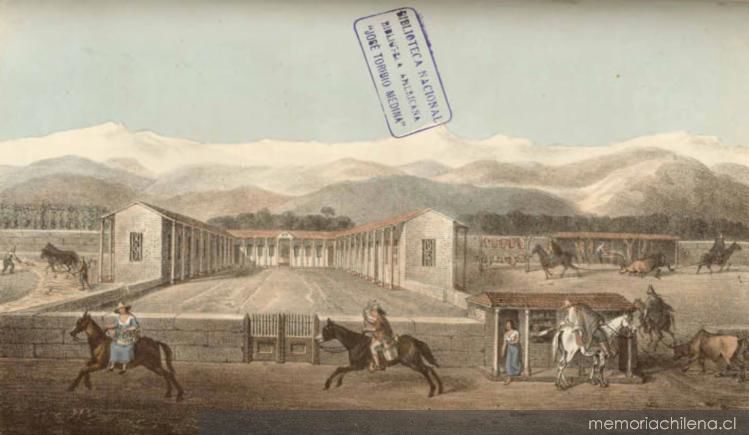

While Latin America achieved independence and preached lofty goals of sovereignty and freedom, practice often varied, especially at the everyday level. One of the most prominent features of colonialism that would endure well into the 20th century were haciendas. Haciendas were large landed estates and important to the Chilean economy. A wealthy landowner took on a paternalistic role for their workers, with the set-up appearing feudal-like according to critics. Agricultural was a large part of the Chilean economy and haciendas made up about 75% of agricultural lands.

Running a hacienda was a large task and one wealthy landowner, Manuel José Balmaceda, wrote a detailed instructional manual on how to run a hacienda. He was the father of Chilean president José Manuel Balmaceda and the manual was originally intended for his children but was eventually published to share with other landowners.

One important aspect of Balmaceda’s guidebook was about how to manage hacienda workers. There was a clear hierarchy of workers. At the bottom were the peons who were hired workers for the day. Above them were inquilinos, who worked on the estate in return for a portion of their own land to cultivate. There was a hierarchy amongst inquilinos with those owning horses and more land versus those with no horse and smaller plots. The inquilinos at the top received the better jobs on the estate while those at the bottom had to “carry out any unforeseen services not considered a formal job.” They were also unable to raise their wages, but they could lower their wages. Balmaceda also sets a limit on how much land each group may receive, which limited their upward mobility, amongst other stipulations and restrictions imposed by the landowners.

The manual took little to no responsibility for their workers. For example, peons, who were at the bottom, had to work from sunrise to sunset with only two half-hour breaks to eat their rationed meals. Additionally, if peons broke or lost any tools, they would have to pay for them. Disruptive behavior, like showing up late, being idle, not following directions, or “encourages others to be insubordinate,” had clear consequences such as a cut in wages, punishments, being fired, and calling the police.

The manual shows the strict measures that were necessary for a hacienda to run efficiently. At the same time, the manual highlights the exploitation of human labor in haciendas and the larger economy in general in which few benefitted at the top while many suffered below. Even though the haciendas endured well into the 20th century, workers would demand for change and agricultural reform to transform the agricultural landscape of Chile.

Works Cited:

Hutchison, Elizabeth Q., Thomas Miller Klubock, Nara B. Milanich, and Peter Winn, eds. The Chile Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Latin America Readers. Durham: Duke University Press, 2014.

Memoria Chilena: Portal. “Hacienda or Country Mansion – Memoria Chilena.” Accessed April 13, 2020. http://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/602/w3-article-99566.html.

By Emily Beuter