Alexander Humboldt was cut from the cloth of the Enlightenment era, becoming a distinguished scientist and explorer of the 19th century (Hamilton). Humboldt’s Eurocentric perspective coincided with the era’s constant search for perfection in understanding. As a researcher, Humboldt’s travels were done not in the name of glory but of scientific discovery and assessment. In his travels throughout the new world, Humboldt’s scientific abilities combine with his political and moral beliefs in his travelogue The Island of Cuba, analyzing the people, commerce, and biology of a vestige of Spanish imperialism.

As noted, Humboldt does not limit himself to his interests in interpreting the world through a holistic, scientific lens. Humboldt, correlating with his proclaimed principles of liberty and political freedom, condemns the institution of slavery within Latin America in the travelogue (Humboldt, 225). Multiple sections of the book draw on slavery, leading Humboldt to illustrate that the system is intertwined with the daily life of Cuba. He describes slavery as horrific and inhumane, yet he only advocates for reform instead of revolution. The rationale of this is placed solely on his criticisms of the violence of the Haitian revolution, worrying of a black-led independent Cuban state (Humboldt, 186-187). This, coupled with his admiration for the plentiful amounts of commerce, highlights the limitations from his perspective as a white European of notoriety. While he approves of the ideals of justice for all men, he condemns black popular sovereignty, and even later in the book highlights Havana’s similarities to European cities (Humboldt, 246). While Humboldt’s views were against the grain of other Enlightenment figures, he still harbors many of the same racial biases regarding Latin Americans, striving for “equality” yet denying their release from European subjugation.

The Island of Cuba’s implications regarding the fear of abolition leading to Black representative rule manifests in the violent domination of the Spanish on the slave population. Criticisms of the slave trade made by Humboldt stem from the fact that Spain was still a willing participant in the slave trade, deemed previously illegal under international law. Fear of an abolitionist plot throughout the first half of the 19th century led to the Ladder Conspiracy, where thousands of people were either arrested or killed by the Cuban government (Rankin). This repression connects Humboldt’s writing to greater perceptions of Spanish colonial rule and Latin America itself. Liberalism became the stronghold ideology in both Europe and Latin America. In both contexts, ideas of liberty and justice clashed with actual liberation from the hierarchy of European society. Humboldt’s travelogue reveals the critical yet apprehensive approach European intellectuals took when assessing the prospects of a Latin America under a liberal yet neocolonial state of being.

Sources:

“Humboldt, Alexander Von (1769-1859).” In Scientific Exploration and Expeditions: From the Age of Discovery to the Twenty-First Century, edited by Neil A. Hamilton. Routledge, 2010.

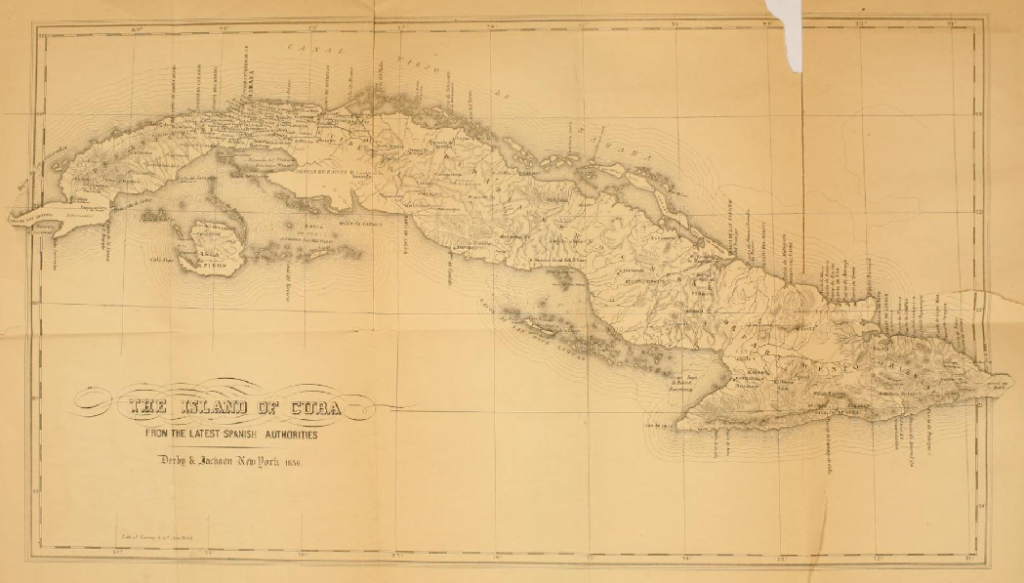

Humboldt, Alexander. The Island of Cuba. Edited by John Thrasher. New York: Derby and Jackson, 1856.

Rankin, Monica A. “Cuba, 1820s to 1900.” In Latin American History and Culture: Encyclopedia of Early Modern Latin America (1820s to 1900), edited by Monica A. Rankin, and Thomas M. Leonard. Facts On File, 2017.