Following La Acta de Independencia de Panamá (1821), Panamá would experience liberation from the Spanish crown but, out of fear of political and economic instability, promptly joined the union of states of Gran Colombia. Therefore, the discussion of Panamá’s post-colonial trajectory is interconnected with Colombia. Simón Bolívar continued the war for independence for many Latin American nations and in his stead, he left Francisco de Paula Santander as president. During his presidency in the 1920s, Santander faced many economic struggles, such as establishing a financial system and funding the state army. Santander utilized his position in power to implement various free trade policies to bolster the Gran Colombian economy. This, in turn, would supply the country with burgeoning economic stability.

Following the end of the wars for independence, Bolívar would return and reclaim the presidency from Santander. Soon their ideological oppositions would result in a rift in the political establishment. Santander would face exile and not return to Gran Colombia until the Bolívar’s death in 1930. Santander would begin his second presidency with a completely new economic ideology. Protectionism is an economic isolationist approach contrary to free trade; Santander used this policy to provide Colombian states and nation businesses growth and lessen foreign competition. Santander’s second presidency would provide Colombia a period of economic stability.

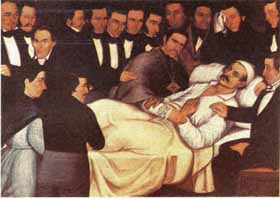

Santander is often recognized as the Caudillo of Colombia. Caudillos are regional strongmen, often gaining political prestige through their wealth and military expertise. The presidencies of Caudillos are often marked with strict rule and corrupt politics, but also widespread admiration and respect from the populous. Many relate Santander as a caudillo because his experience during the wars for independence, fighting alongside Bolívar, but also his corrupted tactics with political power, such as the execution of an entire jail that housed Spanish prisoners of war, his selling of federal offices to political allies, and even a conspiracy to assassinate Simón Bolívar. Regardless of his corruption, Santander was highly beloved and respected by his constituents. One can take notice of these qualities by observing paintings of Santander that display the citizens’ open affection and regard for Santander. One important painting to note is Luis García Hevia‘s Death of General Francisco de Paula Santander (1840). In this portrait, Santander is surrounded by politicians, business owners, church patrons, and commoners. Hevia encompasses the admiration that many Colombian citizens held for Santander by depicting the sorrow in their faces in the wake of his passing. This sorrow stems from the deep-seated feelings of commendation by Colombian citizens. And with those citizens, Panamanians are included.

Works Cited:

Hevia, Luis García, ”Death of Francisco de Paula Santander,” painting, May 6th, 1840, Ganger Historical Picture Archive

Bernal, Ricardo Acevedo, “Francisco de Paula Santander,” oil painting, 1917, House of Nariño, Bogotá, Colombia

Salas, Antonio, “Portrait of Francisco de Paula Santander,” painting, n.a., De Agostini Editore

Huck, Eugene R. “Economic Experimentation in a Newly Independent Nation: Colombia under Francisco De Paula Santander, 1821-1840.” The Americas 29, no. 1 (1972): 17-29. Accessed February 28, 2020. doi:10.2307/980534.

Havrila, Christina. “Caudillos in Latin America: Santander & Páez.” Medium. Medium, October 23, 2016. https://medium.com/@havrilacl/caudillos-in-latin-america-santander-p%C3%A1ez-95fa56e275f6

By Peyton O’Laughlin