Simón Bolívar, Address to the Constituent Congress of Bolivia

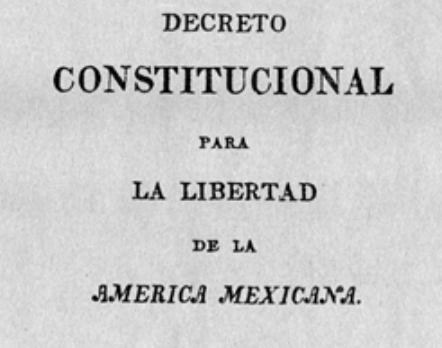

This address was given by the revolutionary leader (and namesake of Bolivia) Simón Bolívar to the Constituent Congress of Bolivia in 1826. Bolívar remains a celebrated historical figure throughout much of Latin America, but in this speech, the contradiction of liberal elites during and after revolutionary struggles. Bolívar was a creole, (a white Spaniard born in the Americas). During the wars of independence, the creole elite sought to cast themselves as part of the diverse group of “Americanos,” which consisted off all peoples born in the Americas. However, the group proved reluctant to relinquish its grip on power in Bolivian society. In this speech we will see allusions to “liberty” and “freedom,” but also the necessity of authoritarian structures. Though this Constitution only lasted five years, it demonstrates the hypocrisy of post-revolutionary liberals and their failures to construct a sustainable government after revolution.

One of the greatest criticisms of the 1826 constitution was Bolívar’s insistence on having the position of President be held for life, and that the President name their successor. This, he argues means that “neither the death of that great man nor the advent of a new president imperiled the state in the slightest” (154). It is also necessary given “the wild nature of our continent” (156).The President, he continues, “can appoint only the officials of the Ministries of the Treasury, Peace, and War; and he is the Commander in chief of the Army”. Bolívar proclaims (not untruthfully) that these powers are “the most narrow ever known” in an executive office. Though the president will control the nation’s army, Bolívar maintains that ample checks on the President’s power will be enough to ensure that this power will not be abused.

The proposed constitution would make some positive advancements as well. The forced labor system for Native Americans called the mita was eliminated. Citizenship was extended only to literate members of society who had an occupation. Though not explicitly racial in its distinction, citizenship was denied to the systemically oppressed populations in Bolivia, especially the indigenous and persons of mixed-race. Slaves were not emancipated either, despite the rhetoric of equality among “Americanos”.

Bolívar, Simon. “Inventing Bolivia” in The Bolivia Reader, Edited by Sinclair Thompson, Rossana Barragan, Xavier Albo, Seemin Qayum, and Mark Goodale, Duke University Press, 2018, pp. 152-159.

Chasteen, John Charles. Born in Blood & Fire. New York: W.W. Norton Co, 2016, pp. 128-132.