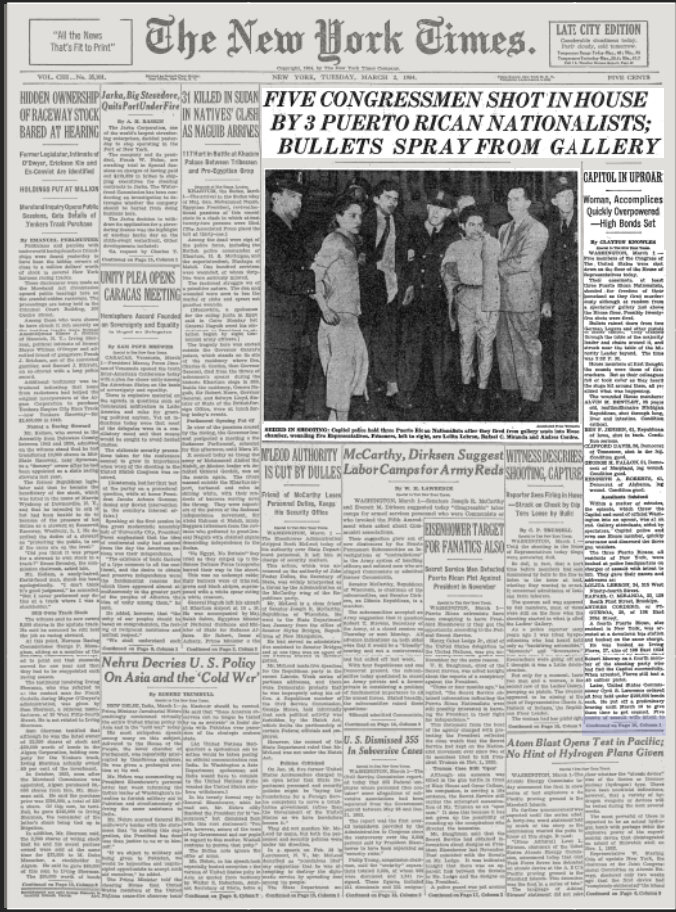

This article on the front page of The New York Times from March 2, 1954 documents the shooting carried out by four Puerto Rican nationalists that occurred in the U.S. House of Representatives the day before. On March 1st, Lolita Lebron, Rafael Miranda, Irving Flores Rodriguez, and Andres Figueroa Cordero had opened fire from the spectators’ gallery while shouting “Viva Puerto Rico” and waving the Puerto Rican flag (The Learning Network). All four shooters were arrested quickly but not before five congressmen were hit by their bullets. The four were also all members of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, which called for independence from the U.S. for Puerto Rico.

Puerto Rican nationalism had been gaining traction over the past decades just as in other places in Latin America. Like in other areas, Puerto Rican nationalism was focused on creating pride and connection in mestizo identities, but Puerto Rican nationalism put an especially heavy focus on critiquing foreign intervention and imperialism and was often associated with the independence movement (Chasteen 2016, 234-235)). After nationalist protests were faced with repression and violence, nationalists in the 1930s began to use more violent tactics to make themselves heard (Anderson). After an anti-independence governor was elected in Puerto Rico in 1947, the so-called “gag law” was enacted, which banned independence protests, nationalist music or speech, and even the Puerto Rican flag (Anderson). Many within the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party were arrested or put under long-term police surveillance, and in 1950, frustrated with the situation, leaders of the party called on members to take to the streets, attacking police stations and U.S. post offices, which they saw as imperialist symbols. A few members even tried to assassinate President Truman when he was staying in San Juan (Anderson).

By 1952, the U.S. government decided to make Puerto Rico a commonwealth rather than a colony, giving Puerto Rican citizens more freedoms, in a hope to appease the nationalist party. While this was a positive move for many, for those wholly focused on independence, it wasn’t enough. This is what led to the shooting in Congress, as pro-independence party members tried to keep the movement alive and in the news. After the arrest of the shooters, the party began to lose its influence and independence faded as a hot-button issue.

Works Cited

Anderson, Jon Lee. “The Dream of Puerto Rican Independence, and the Story of Heriberto Marín.” The New Yorker, December 27, 2017. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-dream-of-puerto-rican-independence-and-the-story-of-heriberto-marin.

Chasteen, John Charles. Born in Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America. 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016.

Knowles, Clayton. “Five Congressmen Shot in House by 3 Puerto Rican Nationalists: Bullets Spray from Gallery.” The New York Times, March 2, 1954. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1954/03/02/83747624.html?pageNumber=1.

The Learning Network. “March 1, 1954 | Puerto Rican Nationalists Open Fire on House of Representatives.” The New York Times, March 1, 2012. https://learning.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/01/march-1-1954-puerto-rican-nationalists-open-fire-on-house-of-representatives/.