By Maureen Hanes

Introduction

Machismo, a distinctly Latin American form of masculinity, is an important aspect of Mexican national identity. Although machismo is often viewed as a singular idea centered around an exaggerated portrayal of masculinity, it is nevertheless difficult to define because there are so many nuances to people’s portrayals of masculinity. While some scholars have previously analyzed machismo in films, the focus has mainly been on comparing portrayals of masculinity across different genres. This paper instead compares cinematic portrayals of masculinity across time and focuses these portrayals within the historical events and issues in Mexico in order to see how expressions of masculinity in Mexico have changed or remained constant over time. With this comparison, I will show how traditional machismo has developed into the modern expressions of masculinity in Mexico today.

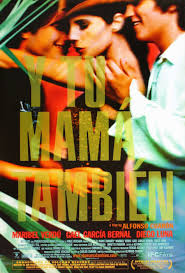

Film is a useful tool for historians, as even if films are not documentaries or historical fiction, all films shot in the real world will capture slices of history through filming landscapes, architecture, people’s mannerisms, clothing, speech, etc. (Deshpande 2004, 4437). Beyond providing realistic historical insights, films also portray the reality that the producer or director wanted to promote, idealistic ideas about how things should be, or critiques on how things should change (Deshpande 2004, 4437). For analyzing machismo, I chose to look at two films. The first film I analyzed was Dos tipos de cuidado, a 1953 film produced during the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema. This film was a huge success and starred some of the most popular movie stars of the time, Pedro Infante and Jorge Negrete. For the second film, I chose Y Tu Mamá También, a 2001 film starring Maribel Verdu, Gael García Bernal, and Diego Luna. This film was also very successful, winning multiple international awards and touted by critics as helping to start a new Golden Age for Mexican film (de la Mora 2006, 174).

These two films make for good comparisons as they are similar in many ways, having been very successful, popular, and starring big-name actors. They also both could be considered “buddy movies,” films about two male friends going on an adventure, often navigating friendship, conflict, and romance (de la Mora 2006, 87). As “buddy movies,” the films focus heavily on masculinity as well, allowing for good comparisons between the two.

Dos tipos de cuidado

Dos tipos de cuidado follows the fictional story of Pedro Malo and Jorge Bueno in a small Mexican town in the early 1950s. At the beginning of the film, Pedro and Jorge are close friends who spend their time together meeting women and attending parties around their town. Jorge is in love with Rosario, Pedro’s cousin, and Pedro is in love with Maria, Jorge’s sister. However, Jorge leaves town for a year, and when he comes back, he discovers that Pedro had married Rosario. Hurt by this information, Jorge begins to date the daughter of a local general and tries to humiliate Pedro every time he sees him.

Pedro eventually decides to confront Jorge’s sister, his true love, but Jorge finds them and threatens to kill Pedro. Before killing him, however, Jorge agrees to listen to Pedro’s story about why he married Rosario, and they then decide to put their differences behind them. They talk to Rosario and Maria and all decide that Pedro and Rosario should divorce and both couples then leave town and marry their original love interests. When the General discovers this plan, he threatens to kill both men for bringing shame on the town and his daughter, who Jorge had proposed to. The couples explain that Pedro had married Rosario because she was raped and had become pregnant, and he wanted to save her from living in shame. They then explain that all the conflict after had just been one misunderstanding. The General forgave them and the new couples were allowed to marry, leaving Jorge and Pedro as good friends once more.

Because this film was made during the Golden Age of Mexican cinema, when the industry was nationalized by the government, it is important to recognize that this film presented the ideas about masculinity that the state hoped to promote. Even though the men in the film are presented as imperfect, emotionally expressive, and generally kind, the moments of aggression and infidelity by the main characters are presented as critical aspects to their masculinity (de la Mora 2006, 80). Also critical to the appeal of the film, and thereby the underlying message, was Pedro Infante and Jorge Negrete’s whiteness (de la Mora 2006, 86). By presenting these characters, and the actors in real life, as the ultimate macho men, the state was thereby promoting white Mexican men as the greatest and most desired form of Mexican men.

Y Tu Mamá También

Y Tu Mamá También is almost a modern-day mirror of Dos tipos de cuidado. The film centers around the relationship between the teenage friends Julio and Tenoch after both of their girlfriends left on a trip to Europe. They soon meet the beautiful wife of Tenoch’s cousin, Luisa (Maribel Verdu) and invite her to go on a road trip with them. After a bad doctor’s visit and learning that her husband cheated on her, she decides to join them. On the trip, the teenagers spend a lot of time talking about partying, their girlfriends, and sex while Luisa tries to teach them about relationships. Eventually, Luisa has sex with Tenoch, which, out of spite, leads Julio to tell him that he had slept with Tenoch’s girlfriend. To try and patch things up, Luisa later has sex with Julio, leading Tenoch to make a similar confession about Julio’s girlfriend. This leads to a big fight between them, which only stops when Luisa threatens to leave the trip.

They decide to repair their friendship and have a nice few days at the beach all together, before one night, after drinking, all three of them have sex together. After waking up naked next to each other, Julio and Tenoch stop speaking to one another. At the end of the film, they meet again a year later, both having broken up with their girlfriends and no longer spending any time together. Tenoch tells Julio that Luisa died of cancer after they returned home from their trip, and then the former friends part ways and never see each other again.

Although this film was considered to be part of a new Golden Age, unlike films from the first half of the 20th century, this film was made without any government funding or support (de la Mora 2006, 174). This allowed the producers and director to have a lot more freedom in terms of subject matter, with the film addressing many sensitive topics such as sexuality, death, political corruption, race, and class (de la Mora 2006, 174). In terms of masculinity, the film offered a critique of traditional portrayals of machismo and showcased the ways in which younger generations are trying to live up to these traditional standards while also beginning to open up to new ideas about gender roles and sexuality.

Machismo Through the Mexican Revolution

To better understand these portrayals of masculinity, it is necessary to look at how machismo has developed and changed in Mexico. Current ideas about gender roles within Mexico can largely be traced back to ideas about gender roles that were developed on the Iberian Peninsula and brought to the Americas during colonization. By the 15th century, ideas about the “perfect Spanish man” had been cemented in Spanish culture through the influence of religious and political leaders who wanted to promote Spanish superiority (Carvajal 2003, 17). Specifically, these leaders hoped to contrast catholic Spanish men with the three main groups that Spain was trying to eradicate at the time: Moors, Jews, and homosexuals (Carvajal 2003, 17). They promoted an image of Spanish men as “Godlier,” that these groups, or more powerful and focused on procreation, which led to masculinity being associated with virility and aggression (Carvajal 2003, 45). When the Spanish arrived in the Americas, they brought these ideas about gender with them, and as indigenous populations were decimated and Spanish influence increased, these ideas became entrenched in Latin America as well.

Gender roles remained largely the same in Mexico until the Mexican Revolution, when gender stereotypes were used as a way to bond all citizens together under Mexican nationalism. Machismo as a kind of “cult of virility” was promoted as a “distinctive component of Mexican national identity,” and was spread by revolutionary leaders to establish a contrast between the majority of Mexican men and the intellectuals, artists, and avant-garde poets who were perceived both as effeminate and against the revolution (de la Mora 2006, 2). Part of the widespread appeal of machismo that led to its adoption across society was also due to the fact that macho men were usually promoted as mestizo (Gutmann 2006, 54).

By the 1920s, politicians and revolutionary leaders had recognized the power of cinema to invent, portray, and circulate machismo as an official state ideology (de la Mora 2006, 3). Since Mexican cinema at the time was funded by the government, leaders were able to easily spread the ideology of machismo nationwide (de la Mora 2006, 2). The state-sponsored national cinema promoted an image of Mexican men as “virile, brave, proud, sexually potent, and physically aggressive,” (de la Mora 2006, 7). Although these ideas about masculinity have existed in Mexico since colonization, Mexican national cinema cemented this idea of machismo as crucial for Mexican men to be considered both Mexican and men. This idea could be seen throughout Dos tipos de cuidado, where the two main characters defined themselves through their womanizing and occasional aggression in the name of their honor or the honor of a woman. In the film, Rosario even openly acknowledged her husband’s infidelity, emphasizing the idea that men have a right and even need to be with multiple women.

Neoliberalism Brings Changing Identities

While Mexican cinema often portrayed an uncompromising, singular view of machismo, the realities of how men across Mexico portrayed and lived their masculinity has often been more nuanced. Traditional machismo in the ways that Golden Age cinema in the 1940-50s portrayed it has become increasingly unattainable for many men, largely due to neoliberalism (Gamlin 2018, 50). As neoliberalism led to increased industrialization, poverty became more widespread and many men felt that the strength and pride they had gained in providing for their families had been taken away (Gamlin 2018, 57). With neoliberalism taking hold in the 1970s, wealth and power had suddenly become key components of machismo, and a stigma was created around being poor (Gamlin 2018, 57). In the traditional machismo of Dos tipos de cuidado, Pedro never lost the respect others in his community even though he was struggling financially. Instead, he was known as a tough rancher and as a man who stood up for his wife, which was more important to his image than his finances. However, with neoliberalism, the traditional image of the macho man, often portrayed as ranchers, farmers, or laborers, increasingly became associated with the lower classes (Gamlin 2018, 57).

Neoliberalism also led to the deterioration of many essential services and safety nets throughout Mexican society, leaving many men without employment or the necessary education to compete in a liberal economy, thereby blocking them from becoming a macho man (Gamlin 2018, 52). Many Mexican men, especially younger generations, turned to the informal sector to make a living, which often results in young men becoming involved in organized crime due to its lucrative business model (Gamlin 2018, 52). With many of these young men unable to fully access the new wealth-based model of machismo, the violence involved in organized crime allows men to express their masculinity through the more traditional traits of strength, bravery, or power (Gamlin 2018, 64). While the increase in organized crime has largely been cited as the driving force behind the increased violence in Mexican society, other researchers believe that individual aggression not tied to organized crime has an equally important role to play.

Aggression often results from a perceived or real assault on the “personhood, dignity, sense of worth, or value,” of a victim (Gamlin 2018, 56). As machismo becomes increasingly unattainable, many men may perceive their inability to reach this ideal form of masculinity as an assault on their personhood. Researchers have pointed to this feeling of marginalization among men as an important causal factor in the staggering numbers of both interpersonal male-to-male violence as well as violence among women (Gamlin 2018, 56).

Male aggression is important to the plot of both films, though rather than related to money, the aggression in both stories stems from the characters feeling as though their romantic advances were thwarted or actual romantic interest taken by another character. Julio and Tenoch in Y Tu Mamá También fight throughout the film over who has the right to have sex Luisa or their girlfriends, and similarly in Dos tipos de cuidado, Pedro and Jorge threaten to kill each other over their feelings for Rosario. Economic violence does play a role outside of the main plot in Y Tu Mamá También however, as the narrator of the film tells the story of men that the two teenagers encounter along their trip. For example, one man they encountered died on his way home from a day laborer job, and one was forced to move when his fishing job was no longer sustainable. In both cases, the men were portrayed as having lost their lives and manhood through their inability to work and provide for their families, which was contrasted by the main plot of Julio and Tenoch trying to discover their own manhood.

Changing gender roles for women have also been pointed to as a factor in increased cases of violence against women by men. Industrialization presented many more opportunities for women to work and provide for their families, and as men have increasingly been unable to uphold their status as the singular breadwinner within a family under neoliberalism, many men feel that their role within the family or even society as a whole has been undermined (Gamlin 2018, 60). While Dos tipos de cuidado presented very traditional gender roles throughout the film, Y Tu Mamá También provided a more nuanced view. Throughout the film, the audience watched as Luisa drinks and smokes alongside Julio and Tenoch and is consistently the one to initiate sexual encounters. However, other scenes emphasize the fact that traditional gender roles still hold strong. After meeting a family at the beach, Luisa spends time cooking and taking care of the young children with the mother of the family while the two boys spend the afternoon fishing and playing soccer with the father.

Modern-day Machismo

In his research in Mexico City, Matthew Gutmann in The Meanings of Macho (2006), found that neoliberalism and globalism had led to a spread of new ideas about gender, especially for younger generations. While many of the older men Gutmann interviewed said that the keys to machismo was connected to “insemination, financial maintenance, and moral authority,” men and boys from younger generations often had a less clear-cut image of what constituted masculinity, tending to see sexuality and gender roles as more fluid (Gutmann 2006, 110).

Even with younger generations opening up to more possibilities in terms of gender and sexuality, some beliefs about machismo remained widespread, including beliefs that real macho men should never cry or show vulnerability, that in order to be a man, one must be able to have many children, and that men have “uncontrollable bodily needs and urges,” Gutmann 2006, 103, 112, 122). Ideas that macho men are all involved in alcoholism, infidelity, wife-beating, gambling, and violence also remained strong within Mexico City communities but were being talked about more frequently and openly (Gutmann 2006, 190).

This divide between old and new generations can definitely be seen when comparing the two films. In Dos tipos de cuidado, moral authority appears to be the greatest characteristic of a macho man. At the end, when Pedro and Jorge revealed that all had been done in order to save the honor of Rosario, their actions were immediately forgiven and both men were viewed once more as the kind of men that others should strive to be. Julio and Tenoch on the other hand appear to struggle a lot more in trying to define their own masculinity. While part of this struggle could be because both were only in their teens, a large part seemed because there was no singular definition of machismo anymore. Both engaged in a lot of drinking, sex, and fighting, yet by the end of the film, both seemed to have lost more confidence than they gained.

Same-sex encounters among men remains a particularly contentious issue. Some of the men Gutmann interviewed saw homosexual encounters as almost a rite of passage, though many distinguished the men who participate as different from men who self-identify as gay (Gutmann 2006, 121). Others felt more comfortable with the idea of gay men, with some admitting to having gay friends, though no one interviewed self-identified as gay, while others interviewed felt that gay men could never be considered true men (Gutmann 2006, 202). This issue was a key part of the plot for Julio and Tenoch. Throughout the film, both characters talk comfortably about having a gay friend, but when they themselves had sex together, they were confused, embarrassed, and questioned their own masculinity. This act between them also serves as the breaking point for their relationship, as they felt unable to be friends after having sex together.

Overall, these films reflect the historical reality that machismo is not a monolithic idea. While some ideas about machismo have remained largely the same even from the period of colonization, machismo has changed over time. Analyzing these changes is important for recognizing that machismo is just as nuanced as any other gender expression. The first significant change happened with the adoption of machismo as part of Mexican national ideology and its subsequent spread through cinema, and the second major change happened with the introduction of neoliberal policy in Mexico. These changes can be seen in the films analyzed, with Dos tipos de cuidado presenting an ideal, post-revolutionary form of machismo and Y Tu Mamá También presenting a more nuanced, complicated, and realistic portrayal of modern machismo.

Works Cited

Carvajal, Federico Garzo. Butterflies Will Burn: Prosecuting Sodomites in Early Modern Spain and Mexico. University of Texas Press, 2003.

de la Mora, Sergio. Cinemachismo: Masculinities and Sexuality in Mexican Film. University of Texas Press, 2006.

Deshpande, Anirudh. “Films as Historical Sources or Alternate History.” Economic and Political Weekly 39, no. 40 (October 2, 2004): 4455–59.

Gamlin, Jennie B, and Sarah J Hawkes. “Masculinities on the Continuum of Structural Violence: The Case of Mexico’s Homicide Epidemic.” Social Politics 25, no. 1 (2018): 50–71.

Gutmann, Matthew C. The Meanings of Macho: Being a Man in Mexico City. Vol. 3. University of California Press, 2006.

Macias-Gonzalez, Victor M. Masculinity and Sexuality in Northern Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, 2012.

Noriega Guillermo Núñez. Just Between Us: an Ethnography of Male Identity and Intimacy in Rural Communities of Northern Mexico. University of Arizona Press, 2014.