By Peyton O’Laughlin

Many recognize Panama as the small, tropical nation located on the isthmus, a narrow strip of land with sea on either side, forming a link between two larger areas of land, of Central America. Panama contains a history of colonization and neo-colonization that can be similarly related to many Latin American countries. I plan to highlight and discuss historical issues that have arisen from such facets. This paper will be an accumulation of my research on Panamanian history. Importantly, I look to engage with the question of how U.S. intervention in Panama’s struggle for independence from Colombia affected the ideological aspirations of the country?

The structure of the paper will appear with historical context, the means of U.S. intervention, and the results of U.S. and Panamanian relationships following the war for independence. The section on historical context will briefly cover Panamanian history as it relates to the encompassing topics of Latin American history. This section will also feature a focus on the political and ideological aspirations of Panamanians leading up to a revolution. The section to follow will cover the reasons for U.S. intervention in the political affairs of Panama and Colombia. The final section provides a comparative analysis of the results of U.S. and Panamanian relationship and the means to which the U.S. gained their canal concessions. The final section is where my historical question will be answered. Ultimately, the purpose of my independent research project is to exemplify intervention in the Panamanian independence struggle as a result of the U.S. imperialism and neocolonial practice. Further, I seek to describe how these implications diverted the purpose of Panamanian insurrection from Colombia to fit the interests of the United States.

Firstly, the matter of European colonization must be addressed as it the beginning of foreign intervention in the Americas. Panama, or the land of, was discovered for Europe by Spanish Conquistador Rodrigo De Bastidas and his crew in 1501. The colonization of the land and indigenous peoples of the Isthmus would promptly follow the arrival of Bastidas. The land was formally navigated and mapped by Bastidas’ first mate, Vasco Núñez de Balboa who, twelve years after the discovery of the land, would be the colonizers to “discover” the Pacific Ocean to the East of the Isthmus. Interestingly, the map-work of Balboa has accustomed him as a national hero in Panamanian culture.

Panama’s long history is often related to that of Colombia. During the colonial era (1492-1810), Panama was merely a province of the Viceroyalty of New Grenada. The liberation of New Grenada during the Latin American wars of independence would allow for Panamanian independence from Spain. As the forces of Simón Bolívar campaigned through Northern portion of South America in the early 19th century, many Peninsulares fled to Panama, but, as battles waged on, the Peninsulares and colonizers began to leave the province of Panama. Panama would witness a “bloodless revolution” as the separatists faced zero causalities when they formally gained independence from Spain. On November 10, 1821, separatist leader José de Fábrega declared Panama as a free state, however, fear of Spanish retaliation to a militarily and economically weak Panama resulted in the new nation joining the Republic of Gran Colombia. The historical trajectory of Panama would be sequestered to Colombia for the remainder of the century.

The decades to follow the wars of independence would prove to be rife with political unrest. The central government of Gran Colombia was weak and disputes between federalists and centralists caused major political rifts that could not be mediated. Gran Colombia would dissolve and the Republic of New Grenada would take its place, Panama would maintain its status as a province to the new governing republic. Political altercations and dissolutions of central governments would be a common occurrence for Colombia and its states throughout the 19th century, this common overturning caused resentful attitudes among the republic’s provinces. Panama, and other regional states, would consistently challenge the central power. Panamanian politician Justo Arosemena would spend his career demanding autonomy for Panama. Arosemena wrote many articles detailing the specific experiences of Panama the most famous of which, El Estado Federal de Panamá (1855), would give Justo Arosemena the title of father of Panamanian nationality. Many of Arosemena’s articles called for the reorganization of Latin American sovereignty and an end to “Yankee intervention,” in Latin America. The declaration for Latin American confederations where states would maintain respective autonomy but function as one to deter foreign intervention was integral to Arosemena’s ideology. Importantly, the writing of Arosemena would become key for Panamanian separatists and it would be called upon countless of times in the latter half of the 19th century.1

By the 1880s, Panamanian insurgents were taking full stride in their movement for succession. Depending on the party in power, the status of Panama was up for debate, either sovereign or department. Panamanians vowed to become completely self-governed and cease their subordination to Colombia. The military might of Colombia was greater than that of the Panamanian insurgents and military occupation of major Panamanian cities became common in the 1880s. Likewise, U.S. troops and naval ships had been dispersed throughout the region to uphold many of their own business and trade interests. The separatist movement was assumed to diminish which would result in Panamanian aspirations of self-governance to end and political purgatory would continue.2

During the time of the Panamanian independence struggle, the United States naval forces were present in many locations of Latin America, the isthmus was no exception. American intervention had taken root almost immediately after the word of the insurgency had reached Washington. The U.S. deployed military services to the isthmus to uphold agreements of neutrality established by the Mallarino-Bidlack Treaty (1846), which allowed the U.S. to provide ample intervention in Colombian affairs when U.S. interests, such as interference in the isthmian/Panamanian railway system. U.S. leaders could not allow civil disputes to disrupt their economic interests. The initial interaction for U.S. involvement was to protect their business ventures. As the armed struggle between Colombian conservatives and liberal factions escalated, U.S. lawmakers, backed by private business owners, began to take the opportunity of Colombia’s unstable situation to seek out other goals, a canal.

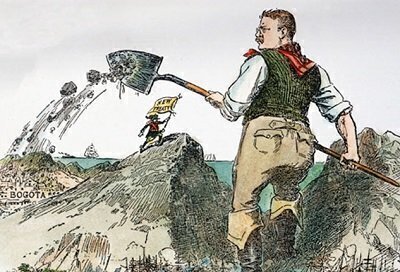

The premise of the canal through the Central American Isthmus had been long sought, even back to the days of Bastidas when he established control over the land. Yet, an overly ambitious Presidency of the United States’ Theodore Roosevelt, whose eagerness for war paralleled that of the rightly named Warhawks of nearly a century prior, and aspects of empire building and explicit ideologies of Western superiority over Latin America had allowed for ample conditions to begin a U.S. overtaking of the Panamanian war effort. To clarify, the induction of “rightful intervention” proposed by the Monroe Doctrine (1823) allowed for the engagement in foreign policy by the U.S. during the 19th century that had resulted in the intrinsic practices and methods depicted with that of neocolonialism and imperialism over Latin American nations. Such examples can be seen with the imposition of U.S. occupation or involvement in internal affairs of Latin American countries, one being the Mallarino-Bidlack Treaty (1846), the same treaty that allowed U.S. interaction in the Panamanian independence struggle. Likewise, the ideology of the superiority of the United States over Latin America was vastly agreed upon. Such sentiments by westerners were common of the time period and can be viewed in works such as Rudyard Kipling’s 1899 poem A White Man’s Burden, in which he addresses the need for U.S. neocolonial practices as a need to save the nations of “colored people” by intervention that would deliver modernization.3

Such aspects of the one exemplified in the paragraph prior are reasons for the establishment of an international environment that implied that it would be immoral and unjust for the U.S. to intervene in the affairs of Latin America, doing so would benefit the U.S. greatly, in terms of military and economy. Further, with the reasoning, the U.S. had great interest in establishing some amount of control over the Central American Isthmus.

Sole ownership of a canal through the isthmus would provide a great addition to the U.S. economy, as they could establish the cost of access fees and travel through a Central American Canal would prove to be quicker and more cost-efficient for a company than to deliver their goods “around the horn,” around Argentina and through the Strait of Magellan. Access to a canal would allow the U.S. to combine its naval forces in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans to become connected. Such an aspect was vastly important as the Spanish-American War, ending in 1898 which was a year before the official beginning of Panama’s fight for independence, as a victory proved the U.S. that they needed to be able to transfer military resource between oceans quicker, especially to maintain control of their newly acquired territories, Hawaii and the Philippines. Likewise, creating an isthmian canal would instantly add great prestige to U.S. engineering as the canal had only been imagined and theorized for 500 years. Only one issue stood between the U.S. and their canal, access.4

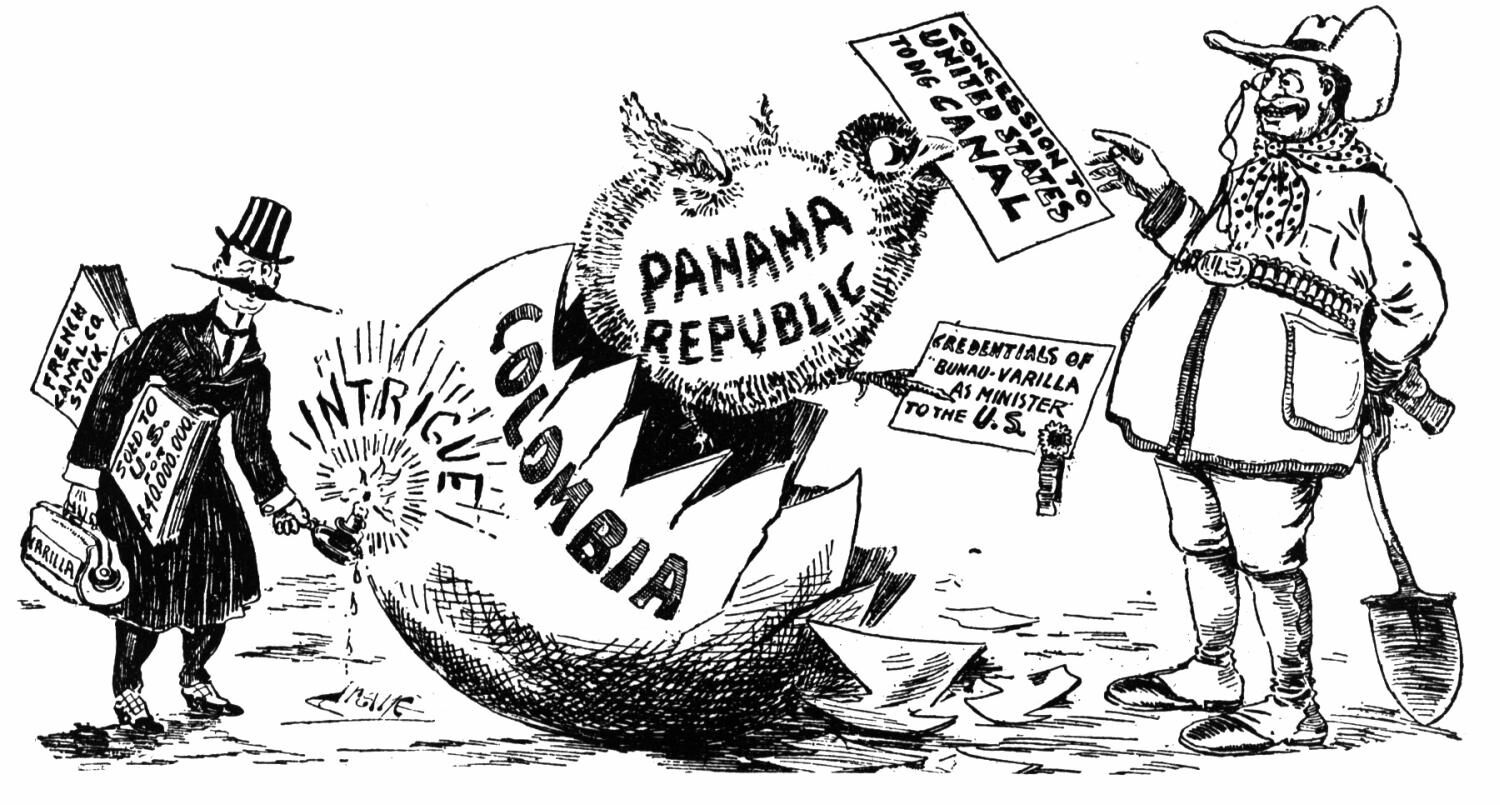

The Colombian government engaged in negotiations with the U.S. over access to the land in Panama for canal building, however, the ratification of agreements often failed. Many times, Colombian politicians in the legislative body failed to ratify treaties such as the Hay–Herrán Treaty (1903). The Hay–Herrán Treaty, if ratified in early 1903, would have supplied the U.S. in access to a canal in exchange for payments and suppression of the Panamanian insurgents. As negotiations with Colombian became ever more tiresome for the U.S., the country decided to divert their assistance to Panamanians in their independence struggle. This choice was calculated greatly, as a victory for the insurgents would allow the U.S. to conduct negotiations with a fledging nation and, in hope, gain greater concessions for a canal.

In sum, the U.S. had their own intentions of neutrality but began to make efforts to seize the means to create a canal. U.S. foreign policy, ideologies of superiority, and an imperious President had allowed the U.S. to create an environment to engage in such practices of intervention between the countries for personal interests. Ultimately, U.S.-Colombian negotiations had become stale and produced the U.S. backed Panamanian insurgency, which was hoped to establish easier canal concessions to the U.S. The U.S. had helped the Panamanians gain independence from Colombia, establishing the Republic of Panama in 1903, and advert a long bloody struggle; however, the implications for the Panamanian ideology would be great.

The means of these concessions are not left to the imagination. The 19th Century is filled with examples of the U.S. gaining great concessions to war through what some call “gunboat diplomacy.” One such example is the “independent nations” of Puerto Rico and Cuba after the end of the Spanish-American War, the result of a U.S. victory allowed the U.S. to lead the end of war negotiations and instill legislative provisions to effectively maintain control over the islands. A similar occurrence appeared with the new Panamanian Republic as much of the negotiations between the U.S. and Panama were led by former Secretary of State John Hay.

The question is not whether Hay had directly threatened to use U.S. military forces to gain adequate concessions for the U.S., but rather how the implications affected negotiations. Without a direct threat, Panamanian politicians could draw the conclusion that the U.S. had assisted in succession for personal interests and, if not satisfied with their spoils of war, could easily take aim for direct annexation. The best course for Panamanians was to concede in fear of another war with a greater combatant than that of Colombia. Likewise, it is described that former Panamanian Ambassador to the U.S., Phillipe Bunau-Varilla, had been the focus of U.S. lobbyists and continued practice of unauthorized negotiations over the canal.5

Most of these aspects of the end of war negotiations would affect not only the treaties but Panamanian legislation as a whole. First, the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty (1903) effectively established a 16 km zone of construction through Panama for the U.S. to create a canal, the area would later be known as the Canal Zone. Agreements on the treaty gave the U.S. allowance to take defensive action to protect their zone. Likewise, provisions such as Article 136 of the Panamanian Constitution (1903) would give the United States, “the right to intervene in any part of Panama, to re-establish public peace and constitutional order,” and the U.S. would exercise the rights of this constitutional article to perform such actions like the deployment of U.S. troops to handle political riots in Panamanian cities or abolish the Panamanian military. The land for canal construction, and access to Panama, was exchanged for payments and rents to Panama. Effectively, the results of the end of war treaties and negotiations between the U.S. and Panama resulted in Panama becoming a de facto protectorate to the U.S. empire.

What remains to be assessed is the question of Panamanian political ideologies. As I stated, Panamanian independence was an ideology of self-governance and autonomy from that of Colombia. Of course, the addition of U.S. assistance in succession resulted in complete separation from Colombia and the establishment of the Panamanian Republic, however, the fact of the matter is Panama’s position in relation to the U.S. Panama had become a protectorate and as such became directed with regards to U.S. interests of building a canal. In sum, Panama’s aspirations for self-governance were diverted due to U.S. intervention. Complete autonomy for Panama and her people would not be granted as a subject to the U.S. and such a reality could be seen in the years to follow as the canal zone became inaccessible to Panamanians and the occupation and deployment of U.S. troops into Panama became relatively common. Panama would not see separation from the U.S. until the late 20th century and the successionist ideology viewed by Arosemena and other Panamanians would not be fully accomplished.

Works Cited:

1: Howland, Douglas and Luise White, The State of Sovereignty: Territories, Laws, Populations. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press, 2009. Pgs 26-29

2: Delgado, Luis Martinez, Panamá: Su Independencia de España, Su Incorporación a la Gran Colombia, Su Separación de Colombia –el Canal Interoceánico. Bogotá: Ediciones Lerner, 1972.

3: O’Toole, G.J.A., The Spanish War: An American Epic-1898. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1984.

Kipling, Rudyard, A White Man’s Burden. New York: Doubleday and McClure, 1899

4: Maurer, Noel, and Carlos Yu, In The Big Ditch: How America Took, Built, Ran, and Ultimately Gave Away the Panama Canal, 55-96. Princeton, New Jersey: Woodstock, Oxfordshire: Princeton University Press, 2011. Accessed May 4, 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctt7sh42.8.

5: Schoultz, Lars, Beneath the United States: a history of U.S. policy toward Latin America. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1998. Pgs 160-165. Accessed on May 4th, 2020. https://archive.org/details/beneathunitedsta00scho/page/160/mode/2up