By Emily Beuter

Introduction

As Cold War tensions ran high, much of Latin America desired change but their efforts were met with wide-spread violence during the mid to late 20th-century. At the same time, indigenous women emerged as activists, including Dolores Cacuango, Tránsito Amaguaña, and Rigoberta Menchú, who is perhaps one of the most well-known as her testimony of the Guatemalan Civil War was transcribed into a book. Many indigenous women’s movements, such as those in Guatemala and El Salvador, emerged from civil wars or political violence. Others emerged from mass political movements, like revolutions and accompanying literacy campaigns. With each rupture, indigenous women began to find a space for their voices. Now that the major political violence of the 20th century has ended in Latin America, where does this leave current indigenous women’s activism?

This project focuses on indigenous women in Latin America and their activism in the 21st century through two case studies, Aura Lolita Chavez Ixcaquic and Guadalupe Vázquez Luna. Indigenous women have long been ignored by governments, scholars, and historians, yet their activism is only growing as they demand change. I argue for complexity in how scholars examine indigenous movements as indigenous women face multiple forms of discrimination, which are reflected in their activism as they fight for social and political issues at varying levels from the local to the international stage. This paper first examines the historiography of indigenous women in Latin America to better understand their background and context. It then moves to an analysis of each case study, Aura Lolita Chavez Ixcaquic and Guadalupe Vázquez Luna, to illustrate how indigenous women face discrimination from various fronts, making their activism multilayered.

Historiography

Scholarly interest in indigenous women and their struggles increased in the late 20th century and early 21st century. I will briefly look at three recent scholarly works to better understand the context of indigenous women today, including: Multiple InJustices by Aída Hernández Castillo, Demanding Justice and Security: Indigenous Women and Legal Pluralities in Latin America edited by Rachel Sieder with multiple authors, and Vernacular Sovereignties by Manuela Lavinas Picq. While each book has its own unique argument, there are some common themes such as complexity, multiple forms of discrimination by various actors, the meaning of indigenous, and how indigenous women fight for a variety of issues.

In Multiple InJustices R. Aída Hernández Castillo brings light to indigenous women’s political struggles in Latin America. Her research is primarily based on her own fieldwork as she argues for complexity in that indigenous women’s “political demands are not limited to an anti-capitalist struggle,” but also include “colonialism, racism, and patriarchal violence.”[1] She attempts to widen the scope of their struggle by not only focusing on their “cultural rights,” but also highlighting their differences to create political alliances and show how indigenous women are redefining law and their rights.[2] She explains how indigenous women’s struggles are unique regarding their conceptions of feminism and duality. Finally, Castillo asserts that indigenous women advocate for multiple issues, such as “material demands for land or services, their cultural rights for an intercultural education and their own justice in terms of indigenous rights.”[3] These are important aspects to consider when researching indigenous women.

Demanding Justice and Security: Indigenous Women and Legal Pluralities in Latin America is a multi-authorial book that “shows how indigenous women have advanced new understandings through their organizational processes, reshaping community, national, and even international law.”[4] The authors analyze various regions in Latin America to illustrate how indigenous women work within their own cultural system of practices to advocate for a variety of issues such as education, prevention of physical and sexual violence, economic independence, and land rights. Similar to the Castillo’s work, this book highlights the difference between indigenous groups and women’s experience within various indigenous groups. Finally, the book situates itself as “public or activist scholarship” with an aim to generate new discussions and to understand that all knowledge is politically and ethically constructed.[5] The authors emphasize that indigenous women are prominent political actors.

In Vernacular Sovereignties, Manuela Lavinas Picq contends that “Indigenous women are not only politically active but are also among the important forces reshaping states in Latin America.”[6] Her book primarily focuses on Ecuador, specifically Kichwa women, as Andean indigenous people have been some of the most politically active groups. She argues that indigenous women have had a long history of activism, but scholars often overlook their roles, explaining that “if Indigenous women are invisible today it is because they are erased from memory by selective histories.”[7] She also argues that “indigenous women do not seek self-determination but instead advocate for autonomy with gender accountability.”[8] Taken together, she asserts how indigenous politics change the political landscape as indigenous groups go from being marginalized by the government to asserting their rights and gaining mainstream political representation.

One crucial argument within the scholarship is that one cannot analyze and understand indigenous women’s activism through Western paradigms. All of these books mention that indigenous women have a completely unique struggle specific to their context and face discrimination and oppression from a variety of fronts. In Multiple InJustices, the author recognizes the overlapping factors of “colonialism, racism, and patriarchal violence,” which lead some indigenous women to look at intersectionality theory, which was developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw, an African American feminist.[9] Intersectionality is “a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects.”[10] Vernacular Sovereignties mentions the same in that “indigenous women suffer discrimination for being indigenous, women, and (often) rural—exclusions that overlap to create a specific geography of oppression,” calling it “politics of intersectionality.”[11] It is also important to recognize that indigenous women face discrimination at various levels, from their families and communities to the national stage.[12] Additionally, the term “indigenous” does not imply a “homogenous group” or “static category,” but rather a population “constantly in process.”[13] Lavina points out that this is evident when thinking about indigenous people in rural areas versus those in urban areas, and those that identify as mestizo, demonstrating a degree of hybridity regarding what it means and looks like to be indigenous.[14] Finally, due to indigenous women’s unique struggles, many indigenous women reject Western views of feminism and gender.[15] Some indigenous women believe that Spanish colonialization and Christianity established patriarchal structures in indigenous communities that are contrary to indigenous concepts of gender such as community equilibrium, duality, and complementarity, but these also carry various connotations and are not stable concepts.[16] All of these aspects add complexity to indigenous women’s struggles.

Much of the research regarding indigenous women was not uncovered until the late 20th century, at the same time much of Latin America was experiencing brutal political violence and revolutions, and indigenous women began to have their voices heard. In recent years, indigenous women’s activism has grown and expanded throughout Latin America. It is essential to understand that there are multiple groups that have various traditions that affect their activism. This project identifies individual case studies of two women from different indigenous groups, so while their cultures are different, they still share experiences of discrimination and systemic inequalities. Nevertheless, indigenous women like Aura Lolita Chavez Ixcaquic and Guadalupe Vázquez Luna, persist in their activism to improve the lives of indigenous women and their communities as a whole.

Case Study #1: Aura Lolita Chavez Ixcaquic

Aura Lolita Chavez Ixcaquic, also known as Lolita, is an activist from Guatemala and a finalist for the Sakharov Human Rights Prize in 2017 by the European Parliament. She fights for the preservation of natural resources and is a leader of the Council of K’iche’ People for the Defense of Life, Mother Nature, Land and Territory.[17] Like other indigenous groups, the Ki’ches suffered violence during the Guatemalan Civil War (1960-1996) and continue to suffer from violence, as Lolita’s testimony reveals through her fight for the preservation of indigenous land.

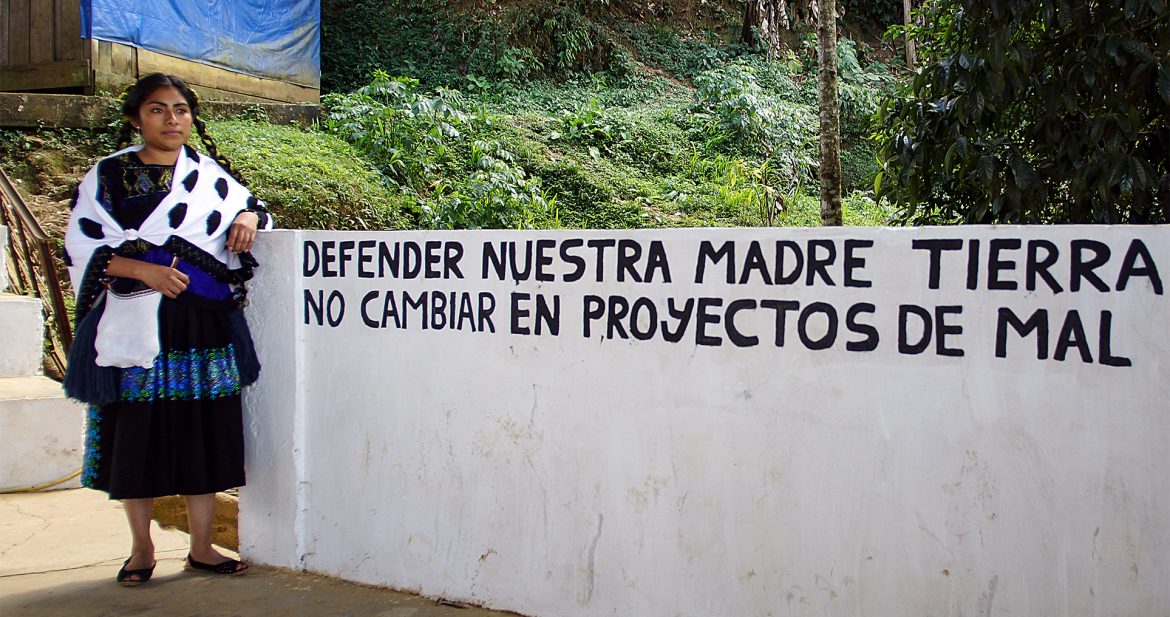

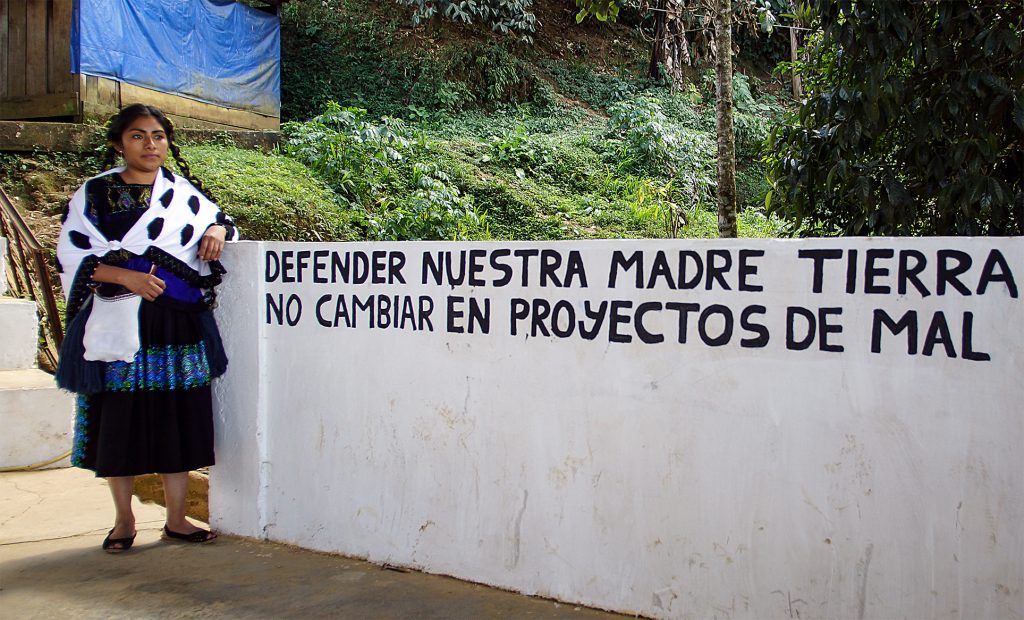

Lolita defends indigenous land in Guatemala from numerous threats. Companies plunder indigenous land for mining, hydroelectric, petroleum, monoculture, logging, and other largescale agricultural industry projects without consent from the indigenous people who reside there.[18] She says that companies “come with an invasive intention, which means dispossession, plundering, death, and destruction” and do not understand their life, models, or proposals.[19] She recognizes the partnerships between companies and the government, explaining that activists are fighting with a worldwide neoliberal economy which prioritizes “business, money, goods, and arms more than humanity, people, or biodiversity.”[20] When people say that her indigenous community wants more royalties from mining, she explains that “the connection is not economic, the connection is about life. We are defending Mother Earth, not for money, but for life.”[21] Women play an especially vital role in carrying this out.

Lolita underscores the importance of indigenous beliefs and the role of women in the fight to protect indigenous land. She notes that women have a special duty to protect the earth, stating, “The women here say that we defend Mother Earth not because she belongs to us, but because we are part of her.”[22] She vocalizes how people view indigenous women in that “they do not consider us individuals with rights, rather they, the multinational companies, see us as an obstacle.”[23] Multinational companies do not understand indigenous ways of life or beliefs as Lolita explains, “We are people who love life and we carry out actions that are focused towards a harmonic coexistence with Mother Earth, with the Cosmos, also resuming inter-generational commitments with our grandfathers and grandmothers.”[24] Unfortunately, these indigenous beliefs violently collide with the consequences of globalization and the goals of neoliberalism.

Like other indigenous activists, Lolita and her group, suffer from constant violence. In June of 2017, she and other members of her group were threatened by ten armed men. Her group had peacefully stopped a truck to “verify if the wood being transported was from illegal logging on their land.”[25] It was illegal, and while escorting the truck to report the incident to authorities, ten armed men approached them and began threatening them, including threats of sexual assault. Her group escaped while the men fired gunshots in the air. Afterward, people reported that the men were looking for Lolita. She knows these threats are not idle; a member of her group was assassinated in 2012.[26] It is clear that political violence continues to be used against indigenous communities and women with threats of sexual violence. Lolita says that these threats have “generated amongst us, particularly among women, a great deal of repression and criminalization. I have suffered several attacks, threats, defamation, persecution, and criminalization by the government.”[27] Her testimony illustrates continued violence against indigenous women and their activism.

In the struggle to preserve indigenous land, the government often sides with companies and in doing so, fails to protect indigenous communities. Lolita says that the government typified her case as “terrorism” because the government claims she is a threat to the national security and political constitution of the country.[28] She says this has greatly affected her because she was known as a teacher but is now known as a terrorist, living with the constant fear of persecution. Repeated threats of violence have forced Lolita to live in hiding, where she continues her fight for her people. She is living in the Basque region of Spain where she received the Ignacio Ellacuría Prize for her work for her people from the Basque government in 2018. Numerous organizations feel that the Guatemalan government is not doing their role in protecting her and fellow group members, demanding that the government step up and protect her and other peaceful protesters. Even amidst violent threats and discrimination, Lolita recognizes waves of progress with various indigenous councils and assemblies, some with more than 27,000 people, and collaboration with the United Nations on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.[29] However, the fight still continues as indigenous women activists work to reclaim what is theirs. Lolita is one of many who recognize her unique status as an indigenous women activist as she fights for land preservation and human rights. Her testimony indicates that violence against indigenous women continues and that women like Lolita, are willing to risk their lives in order to fight for her people.

Case Study #2 Guadalupe Vázquez Luna

Guadalupe Vázquez Luna, also known as Lupita, is an activist from Mexico and part of the Tsotsil community, representing the Alto-Centro region in Chiapas as a member of the Indigenous Council of Government. She is also the first Tsotsil woman to receive a baton from the Las Abejas, a Mayan Christian activist group. She is a survivor of the Acteal massacre, which killed her mother, father, five brothers, grandmother, and uncle. She advocates for solutions to issues such as violence, forced disappearances, and other human rights violations. She encourages others to collaborate and join forces, especially as the government fails to protect indigenous communities.[30] Like Lolita, Lupita’s experience is filled with political violence and discrimination as she engages in activism as an indigenous woman.

Political violence changed Lupita’s life at 10 years old, when the Acteal massacre occurred. “My life transformed,” she reflects.[31] Prior to the Acteal massacre, she remembers a relatively happy childhood, growing up surrounded by nature and her father retelling stories of their enslaved ancestors.[32] Still, her community was not ignorant of the conflicts and was aware that paramilitary groups were training nearby. When they started burning indigenous houses, they lived in constant fear but did not retaliate with violence.[33] Her father, a prominent moral leader, had strong faith and encouraged the community to fast and pray, even when the paramilitary men arrived. It was while they were praying that the paramilitary men began shooting on December 22. Lupita witnessed her mother dying and had to be prodded by her father to run for her life. In total, she lost nine family members, including both her parents. At a young age, Lupita had the responsibility of raising her younger sisters. She recalls that it “was a strong change in my life because after the massacre, I had to stop being me…the little girl became a woman who had to look over her sisters.”[34] Lupita’s life has never been the same since the massacre.

Like other violence against indigenous communities, justice has not been served; those responsible for the Acteal massacre were released from jail. Lupita says that “the government released them and awarded them, because in this country you can kill and leave rewarded. That is what we have seen and have lived.”[35] Since that day, she has continued to fight for justice for the victims of the massacre and worked to keep the memory alive. She frequently shares her testimony at remembrance ceremonies, rallies, and other gatherings.[36] Recently, her testimony was included in a report to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights for a pending resolution.[37] Her testimony reveals how political violence continues against indigenous communities and the government fails to take responsibility. However this is not the end of indigenous plight as they face discrimination in other aspects of life such as education.

Lupita also sheds light on the limits of education for indigenous women, reflecting on her own experience. She explains, “I was already a rebel before Acteal,” as she convinced her father to allow her to continue with school with her good grades, even though her older sisters worked in the fields.[38] After the massacre, their whole community was displaced and there was no school in the community. When a school did open, she sent her younger sisters. Eventually one of her brothers asked her if she wanted to continue with school and she did, finishing primary and secondary school, and eventually enrolling in a preparatory school on a scholarship. She said she faced machismo along the way, as her brother initially did not grant her consent for reasons relating to marriage. She persisted, but it was difficult. While the scholarship paid for tuition and board, there was not enough money for food and transportation. She lived alone and her grades dropped, so she left, saying, “In the first semester I dropped below average, I was disappointed in myself and I couldn’t take it anymore. I left school with tears, but I had no other option.”[39] Her testimony demonstrates how indigenous women’s access to education is limited due to both family-culture and institutional discrimination. Education was not the only place where Lupita encountered machismo, propelling her to fight against it.

Even though Lupita strongly identifies as a mother, she also works to defy subscribed gender roles. She has worked with the Zapatistas, a left-wing militant group, to challenge “traditional women’s roles dictating the laws of etiquette, marriage and submissiveness.”[40] This is also evident in her own life. At 19, she met a man and had two children with him, going against the tradition of asking her brothers’ permission for marriage. She continued with her activism, which people questioned because they kept her away from her duties at home. Eventually Lupita and her partner separated as she said he was drunk and jealous.[41] She explains that machismo “is very strong in the communities. There are men that feel they are the owners of women…There is a lot of alcoholism and beatings against women. It is also very sad how we have been put into that mentality that a woman is not worth anything, cannot go forward alone, and is nothing without a man. It is difficult to make women in the community understand that this is not the case.”[42] She says that few women recognize their value, giving credit to women artisans who realize that they can gain their own income. She says that “It is also about raising awareness that we should not depend on men.”[43] This is exactly what Lupita does in her career and as an activist. She herself is a single mother who works as an embroiderer in a women’s craft cooperative.

Today, Lupita is a prominent activist for the indigenous community advocating for a variety of causes such as ending political violence, providing indigenous women access to education, and challenging machismo. Her activism reflects the various forms of discrimination indigenous women face. She also defends land preservation as, like other indigenous communities, “megaprojects” take over their land and resources without consultation. Lupita blames the government for selling their land and resources for wealth, like water, gold, oil, petroleum, and other mining activities. As a council member, she believes her purpose is to bring light to long-standing problems because “the government is not interested in solving them or putting an end to them.”[44] To raise awareness, she talks with indigenous communities and shares her own experiences and experiences of others with the council. As the government fails to protect indigenous communities, she encourages indigenous people to collectively organize as “one tree is easy to knock down but the crowded tree is not so easy.”[45] Lupita is an example of a resilient woman who recognizes the various struggles that indigenous communities face regarding political violence, education, machismo, and land preservation. Amid tremendous difficulties and discrimination, Lupita continues to call for change while challenging the societal and political order of indigenous women.

Conclusion

Both of these case

studies highlight indigenous women’s activism in the 21st century. As

Lolita and Lupita demonstrate, indigenous women are multifaceted, as they face

discrimination at various levels, which is reflected in their activism as they

fight for multiple issues at once. This includes political violence, land

preservation, megaprojects, education, and machismo. Their testimonies

reveal the inadequacies of the government and companies to take responsibility

for violence and injustice against indigenous communities. Indigenous women are

some of the leading activists, vocalizing their concerns and calling for justice.

Even when their activism is met with violent reactions from companies and the

government, they persevere. This project aims to raise awareness about

indigenous women as it is critical that scholars, politicians, and the media

pay more attention to their concerns. Indigenous women activists are changing the larger societal and

political landscape in Latin America, and their voices are only becoming

louder.

Bibliography

Columbia Law School. “Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality, More than Two Decades Later.” Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.law.columbia.edu/pt-br/news/2017/06/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality.

Flores En El Desierto. “Guadalupe Vázquez Luna Soy lo que soy y lo que me hizo la vida,” January 19, 2018. https://floreseneldesierto.desinformemonos.org/guadalupe/.

Front Line Defenders. “Aura Lolita Chavez,” May 20, 2016. https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/en/profile/aura-lolita-chavez.

Gariwo Garden of the Righteous Worldwide. “Aura Lolita Chavez.” Accessed April 17, 2020. https://en.gariwo.net/righteous/the-righteous-biographies/holocaust/exemplary-figures-reported-by-gariwo/aura-lolita-chavez-19643.html.

Greens/EFA. “Lolita Chávez: Defending Human Rights in Guatemala.” Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.greens-efa.eu/en/article/news/lolita-chavez-defending-human-rights-in-guatemala/.

Guadalupe Vázquez Luna, Concejala Tsotsil. Comunidad de Acteal, Chiapas. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=867u-WT4Yfc.

Hernández Castillo, R. Aída. Multiple Injustices: Indigenous Women, Law, and Political Struggle in Latin America. Tuscon: University of Arizona Press, 2018.

Inciativa mesoamericana de mujeres defensoras de derechos humanos. “#WHRDAlert GUATEMALA / Gunmen Threaten Aura Lolita Chávez and CPK.” Accessed April 17, 2020. https://im-defensoras.org/2017/06/whrdalert-guatemala-gunmen-threaten-aura-lolita-chavez-and-cpk/.

Lolita Chávez: «No Nací Para Ser Asesinada, Violada o Torturada, Sino Para Ser Una Mujer Libre». Hala Bideo. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vzbq9oUBtlM.

Marlo, Mario. “Las mujeres Abejas de Acteal, dignas y rebeldes.” Somos el Medio (blog), August 2, 2018. https://www.somoselmedio.com/2018/08/02/las-mujeres-abejas-de-acteal-dignas-y-rebeldes-solapas-principales-vista/.

Multiple Exposure: Guatemala – Aura Lolita Chavez. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=5&v=7GxpgUiNhwI&feature=emb_logo.

Picq, Manuela Lavinas. Vernacular Sovereignties: Indigenous Women Challenging World Politics. Tuscon: University of Arizona Press., 2018.

Radio Zapatista. “Masacre de Acteal.” Accessed April 21, 2020. https://radiozapatista.org/?tag=masacre-de-acteal.

Sieder, Rachel, ed. Demanding Justice and Security: Indigenous Women and Legal Pluralities in Latin America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2017.

TeleSUR English

News. “Meet Latin America’s Most Prominent Indigenous Female.” Accessed

February 28, 2020. https://www.telesurenglish.net/news/Meet-Latin-Americas-Most-Prominent-Indigenous-Female-Icons-20180305-0027.html.

[1] R. Aída Hernández Castillo, Multiple Injustices: Indigenous Women, Law, and Political Struggle in Latin America (Tuscon: University of Arizona Press, 2018), 5.

[2] Hernández Castillo, 6.

[3] Hernández Castillo, 10.

[4] Rachel Sieder, ed., Demanding Justice and Security: Indigenous Women and Legal Pluralities in Latin America (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2017), 21.

[5] Sieder, 16.

[6] Manuela Lavinas Picq, Vernacular Sovereignties: Indigenous Women Challenging World Politics (Tuscon: University of Arizona Press., 2018), 5.

[7] Picq, 26.

[8] Picq, 11-12.

[9] Hernández Castillo, Multiple Injustices. 13.

[10] “Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality, More than Two Decades Later,” Columbia Law School, accessed May 5, 2018, http://www.law.columbia.edu/news/2017/06/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality.

[11] Picq, Vernacular Sovereignties, 8-9.

[12] Sieder, Demanding Justice and Security, 7.

[13] Picq, Vernacular Sovereignties, 15-16.

[14] Picq, 17-18.

[15] Hernández Castillo, Multiple Injustices, 14.

[16] Sieder, Demanding Justice and Security, 5-9; Hernández Castillo, Multiple Injustices, 14-16.

[17] “Aura Lolita Chavez,” Gariwo Garden of the Righteous Worldwide, accessed April 17, 2020, https://en.gariwo.net/righteous/the-righteous-biographies/holocaust/exemplary-figures-reported-by-gariwo/aura-lolita-chavez-19643.html; “Meet Latin America’s Most Prominent Indigenous Female,” TeleSUR English News, accessed February 28, 2020, https://www.telesurenglish.net/news/Meet-Latin-Americas-Most-Prominent-Indigenous-Female-Icons-20180305-0027.html.

[18] “Aura Lolita Chavez,” Front Line Defenders, May 20, 2016, https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/en/profile/aura-lolita-chavez; Multiple Exposure: Guatemala – Aura Lolita Chavez, accessed April 17, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=5&v=7GxpgUiNhwI&feature=emb_logo.

[19] Multiple Exposure.

[20] Lolita Chávez: «No Nací Para Ser Asesinada, Violada o Torturada, Sino Para Ser Una Mujer Libre» (Hala Bideo), accessed April 17, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vzbq9oUBtlM.; translation by the author.

[21] Lolita Chávez.

[22] Multiple Exposure.

[23] Multiple Exposure.

[24] Multiple Exposure.

[25] “Aura Lolita Chavez,” May 20, 2016.

[26] “Aura Lolita Chavez.”

[27] Multiple Exposure.

[28] Multiple Exposure.

[29] “Aura Lolita Chavez”; “#WHRDAlert GUATEMALA / Gunmen Threaten Aura Lolita Chávez and CPK,” Inciativa Mesoamericana de Mujeres Defensoras de Derechos Humanos (blog), accessed April 17, 2020, https://im-defensoras.org/2017/06/whrdalert-guatemala-gunmen-threaten-aura-lolita-chavez-and-cpk/; “Lolita Chávez: Defending Human Rights in Guatemala,” Greens/EFA, accessed April 17, 2020, https://www.greens-efa.eu/en/article/news/lolita-chavez-defending-human-rights-in-guatemala/.

[30] “Meet Latin America’s Most Prominent Indigenous Female.”

[31] Guadalupe Vázquez Luna, Concejala Tsotsil. Comunidad de Acteal, Chiapas, accessed April 17, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=867u-WT4Yfc.; translated by the author.

[32] “Guadalupe Vázquez Luna Soy lo que soy y lo que me hizo la vida,” Flores En El Desierto (blog), January 19, 2018, https://floreseneldesierto.desinformemonos.org/guadalupe/.

[33] Guadalupe Vázquez Luna, Concejala Tsotsil. Comunidad de Acteal, Chiapas.

[34] Guadalupe Vázquez Luna, Concejala Tsotsil. Comunidad de Acteal, Chiapas.; translated by the author.

[35] “Guadalupe Vázquez Luna Soy lo que soy y lo que me hizo la vida.”; translated by the author.

[36] Mario Marlo, “Las mujeres Abejas de Acteal, dignas y rebeldes,” Somos el Medio (blog), August 2, 2018, https://www.somoselmedio.com/2018/08/02/las-mujeres-abejas-de-acteal-dignas-y-rebeldes-solapas-principales-vista/; “Masacre de Acteal,” Radio Zapatista (blog), accessed April 21, 2020, https://radiozapatista.org/?tag=masacre-de-acteal.

[37] “Guadalupe Vázquez Luna Soy lo que soy y lo que me hizo la vida.”

[38] “Guadalupe Vázquez Luna Soy lo que soy y lo que me hizo la vida.”

[39] “Guadalupe Vázquez Luna Soy lo que soy y lo que me hizo la vida.”

[40] “Meet Latin America’s Most Prominent Indigenous Female.”

[41] “Guadalupe Vázquez Luna Soy lo que soy y lo que me hizo la vida.”

[42] Guadalupe Vázquez Luna, Concejala Tsotsil. Comunidad de Acteal, Chiapas.; translated by the author.

[43] “Guadalupe Vázquez Luna Soy lo que soy y lo que me hizo la vida.”

[44] “Guadalupe Vázquez Luna Soy lo que soy y lo que me hizo la vida.”

[45] Guadalupe Vázquez Luna, Concejala Tsotsil. Comunidad de Acteal, Chiapas.; translated by the author.