Progress or Neocolonialism?

Introduction

During the 19th Century, Chile transformed itself from a colonial society to a modern country with large scales of economic development and immigration. Even though Chile is located in the edge of the Southern Cone, the country attracted large numbers of merchants, investments and immigrants from European countries such as Germany, France, Spain and Britain. Great Britain was the major trade partner with Chile during the 19th Century. Besides the trade relationship, many British engineers worked on Chilean mining and railroad projects to improve national infrastructures.[1] As Britain and Chile developed a strong relationship diplomatically and economically, large numbers of British immigrants arrived in Chile with their families under favorable government policies.[2] In South America, Chile has the largest number of British descendants that takes 4% of the general population nowadays.[3]

Great Britain played an important role in the early stage of Chilean national development in economy through trades, infrastructures and immigration. British legacy lasts until this day economically and culturally. For example, the British Arch in downtown Valparaiso recognized the British community with writings on the marble saying “la colonia británica”. “Colonia” in Spanish has ambiguous meanings, as this word either refers to community or colony. This word “colonia” has raised an important question about the relationship dynamics between Chile and Britain. We could see asymmetrical power between Chile and Great Britain during the 19th Century, as Great Britain had benefited more from the bilateral trade relations. British residents in Chile dominated economic activities such as financial services and exports. Some scholars such as Gallagher and Robinson have argued that British economic influence in Chile was another form of imperialism and colonialism because Britain always tried to dominate the market with informal control.[4] On the other hand, other scholars have praised British investment as an example of modernizing Chile because of their involvement in business and infrastructures.[5]

British economic and cultural influence in Chile is not well presented in Modern Latin American history. Many British and Chileans are not aware of the level of British influence in Chile during the 19th Century. Moreover, the foreign relation between these two countries is still controversial regarding modernization and neocolonialism. In this project, we are going to review the 19th Century British and Chilean history of trade, infrastructures and immigration. At the same time, we will analyze the relationship dynamics between these two countries. Primary sources such as 19th Century original photos, English newspaper articles and advertisements, and politicians’ statements will be used. Secondary sources such as 19th Century Studies academic articles, National Library of Chile and British Library digital humanities sites will guide us through this project.

Trade and Economic Progress

During the 18th Century, Great Britain gradually transformed from small textile production and workshops to mass factory productions. At the end of the 18th Century, watermills, windmills and horsepower were replaced by steam and coal. In the early 19th Century, Great Britain had 2000 engines used at factories.[6] After the first Industrial Revolution during the 18th and 19th Century, Great Britain was looking for foreign markets by selling finished goods such as steam engines, textiles, hardware and mining equipment to their partners countries. Great Britain was leading in the global trade because they were more efficient and sold their goods at a cheap price while purchasing local goods in other countries.[7] Latin American countries were their customers after they had overthrown the Spanish crown and gained liberty in trades. Chile was one of the countries that purchased those British finished products while exporting primary materials such as wheat, copper, gold and nitrate in exchange.[8] It was a strategic plan for Chile to establish trade relations with Great Britain because their traditional partner countries such as Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil and Peru could not recover quickly economically after their Independence War.[9]

British-Chilean foreign trade relation was established under mutual government support. For Chile, a new independent country that gained its independence in 1818, it was important for them to gain foreign recognition and establish trade. Antonio José de Irisarri who was the Chilean Ambassador in England and France believed that Chile needed support or recognition from European countries to develop a country that was stagnated in the colonial era.[10] Thus, he proposed establishing trade relations either with France or Great Britain. In his letter Bernardo O’Higgins in 1817, he questioned that “suppose that it were necessary to offer to England, or to France ten years of exclusive trade with us in return for their decision in our favor? What would it be that we would lose in this?”[11] Between these two countries, the O’Higgins government favored Great Britain as their major trade partner. In 1819, Chile and Great Britain set up a formal trade relation when Irisarri traveled to Great Britain during O’Higgins presidency. From the first formal meeting, Irisarri requested British loans and trade deals with Great Britain. The plan was finalized in 1822, and Great Britain loaned 1-million-pound sterling to Chile.[12] From the British official visit in 1825, the consuls showed the high levels of support to this bilateral relation because Chile is steady and profitable.[13] Chile in the early years took advantage of the diplomatic relationship with Great Britain to strengthen their contact with the global market.

With the mutual government support for free trades between the two continents, Chile quickly attracted large numbers of British merchants in global trades and local businesses. British merchants arrived in Chile with their occupational background and knowledge in raw material exports, finished goods exports and technology. Some sent their business partners and contracted partners to Chile.[14] For British merchants, Chile was one of their options for settlements when they were “in route for some other country or to nowhere in particular, and who fell in love with Chile and stayed to settle there.” Then, they either brought their families or married to other immigrants or Chileans.[15]

These British merchants in Chile were the group of people in “high trade (alto comercio)” and controlled large portion of exports and imports.[16] Valparaiso attracted large numbers of British merchants to start their businesses there because of its favorable geographical location by the Pacific Ocean.[17] Like other European companies, British companies established local branches or agencies in Valparaiso.[18] Moreover, Chilean government showed economic support by building warehouses and made trade goods duty free after 1830.[19] For example, Williamson-Balfour Company that was established in Liverpool for nitrate and wool exports and expanded its branch to Valparaiso in the following year. Financial services were established to support the growth of mining material trades as well. The Anglo South American Bank was created by Colonel Thomas to deal with mining in the northern Chile.[20] The bank initially used the name “Bank of Tarapaca and London”, and later the Valparaiso branch was established in 1888.[21] Rich primary materials in Chile were valuable to Great Britain in the 19th Century. Therefore, transnational business offices were established there.

The trade between Chile and Great Britain was growing. From 1818 to 1828, 16 merchants were British amongst the 40 merchants.[22] Under the O’Higgins presidency, British exported 28,888-pound sterling worth of goods to Chile in 1817, and those goods increased its value to 443,580-pound sterling in 5 years.[23] The second half of the 19th Century was the boom of British commerce, as the number of British importers grew from 17 in 1849 to 38 in 1895, which took the majority in Valparaiso amongst all European importers.[24] Great Britain kept earning large profits from the bilateral trade relation. During 1814-1818, British exported goods earned approximately 2.8-million-pound sterling. In 1835, they earned 6.4-million-pound sterling in total.[25] By the end of the 19th Century, British share of imports and exports in Chile took up to 67.1% and 43.3% respectively.[26] Great Britain was the major trade partner that dominated the Chilean market until the US started to take over in the 20th Century.[27]

Infrastructures and Development

Mining was the main economic activity since the colonial era. After the Revolution, Chile continued to take advantage of the mining resources such as silver, copper and nitrate to develop their economy. These resources contributed to the global economy drastically. In 1879, Chile produced 30% of the world’s copper, which was the major production back in the time.[28] The Constitution of 1833 modified the existing constitution so that the country could consolidate power at a greater level politically and economically.[29] As part of the national development plan under this constitution, the Minister of Energy Diego Portales highlighted the importance of exporting mining materials as a crucial part. Under Portales’s mining project development plan, Inspector Juan Godoy found mineral resources near the city of Copiapó in the desert of Atacama. Copiapó soon became a commercial center because of the rich primary resources, but the city needed railroads to transport their minerals to the port more efficiently. [30] Therefore, the first railroad project between Copiapó and Caldera was built in 1851 to connect the mining town and the coastal city under an American engineer named William Wheelwright’s supervision.[31] Despite the line Copiapó-Caldera was built, not the whole Northern Chile was completely developed. A news report from the English newspaper Valparaiso and West Coast Mail on August 19 of 1871, it was shown that

“mineral riches of the north will never be opened up till a cheap and efficient kind of railroad is devised for bringing the ore down to the coast for shipment…that such a system will never be carried through by any government goes out of its due course…the State has no capital of its own…in a paper on the “Railways of the Future,” read by Mr. Fairlie, author of the narrow-gauge system, before the British Association at Liverpool. He says: “Railways can be made cheaply, and, at the same time, thoroughly efficient; and those who aver to the contrary are, in fact, enemies to progress and civilization.”[32]

Chile realized its incapacity in capitals for their infrastructure projects, but foreign investments could help them with advanced technology. Thus, the Chilean government was looking for capitals and skilled engineers with majority of them from Britain and the US.[33]

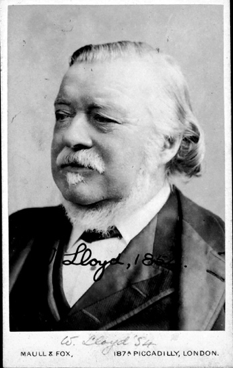

Great Britain was the first country that used steam engines for trains in the early stage of industrialization.[34] Moreover, Great Britain had large numbers of talented engineers. Under the network of engineers from the Institution of Civil Engineers in Britain, many of them were recommended by their fellows to build projects in Asia, Africa and the Americas.[35] Chile was one of those countries in 19th Century that hired large numbers of British engineers. William Henry Lloyd was one of the British engineers who participated in these infrastructure projects in different countries such as the West Indies, Argentina, Mexico and Chile throughout his career. Lloyd worked in Chile during the 1850s and 1860s after he was recommended by his fellows from the Institution of Civil Engineers.[36] One of his significant projects was the railway between Santiago and Valparaiso under the Chilean government contract, and the whole route was not open until 1863.[37] The Santiago-Valparaiso railway project was a huge breakthrough in Chile, as there was only one ancient road that was built in the colonial era to transport goods cargos before the railroads. The construction project was a huge challenge when the engineers had to be accurate about the curvature of tunnels and the use of dynamites in between steep mountains.[38] Lloyd was one example of British diaspora in Chile and helped the economic growth.

Good infrastructures were crucial for Chile to improve their efficiency in transportation of agricultural goods and minerals. Chilean government was supporting foreign investment in order to develop their infrastructures. Under Manuel Montt’s government in the middle of the 19th Century, one politician named Benjamín Vicuña McKenna praised the railroad projects as a combination between “foreign science” and “national industrial capital”.[39] We could see that the Chilean government knew the importance of following the early stage of modernization and progress under the post industrial revolution era. With the contribution of British capitals, Chile advanced quickly with solid infrastructures. As a result of the railroad constructions, they could transport their mining materials quickly from remote towns to coastal cities. Then, the primary materials were shipped to Europe from the Pacific Ocean. Infrastructures helped Chile progress under a tight transportation network.

Immigration

Besides the foreign trades and infrastructure projects between Chile and Great Britain in the 19th Century, foreign immigration was growing because Chile provided new economic opportunities for them. To attract large numbers of immigrants, the Chilean government offered many economic incentives for merchants, residents and their family members. In 1818, Ambassador Irisarri ordered free transportation for them to arrive at Santiago.[40] Later in the years, the Chilean government expanded the land to the southern part of the country and attracted many foreign immigrants as well. Under José Joaquín Pérez’s presidency, he finalized the plan of developing the Magellan Colony in 1867. The Strait of Magellan was valuable from the Chilean government’s perspective because this strait connects both Atlantic and Pacific Ocean, which many boats had to pass through before the construction of the Panama Canal.[41] For those European immigrants who were willing to move there, the government offered free transportation, education, importation of personal items, healthcare, an allowance or pension of five dollars, proportionate distribution of animals and fifty cents per acre land sale.[42] British immigrants were the group of people who received many benefits from the Chilean government and became influential in the local communities. They have contributed to the local communities with their British technical and economic background, as well as brought cultural diversity to some Chilean regions.

Even though some British immigrants stayed temporarily in Chile, large numbers of them chose to reside in the country such as Patagonian and Valparaiso region. In 1885, British residents in the Magellan region had around 291 out of the 2085 inhabitants, which took up to 14% of the foreign immigration population. They controlled 70% of the land during the second in the region during the 19th Century. Taking advantage of their geographical location in the Strait of Magellan, British immigrants built freezing plants and exported mutton carcasses.[43] Sheep farming became a major economic activity in the colony, which attracted large numbers of labor from England and Scotland through family connections. British immigrants introduced new methods of preserving meat that they used in their home country to the colony. Besides their commercial and industrial contribution to the Patagonian region, they have established local businesses such as the Magallanes Telephone Company, Royal Hotel and L.L Jacobs English imports and general bouquet house.[44] British immigrants had developed the southern Chile with their skills and hard work in agriculture, industry and technology, which transformed the Patagonian region to a land of opportunities.

British immigrants not only expanded their economic influence, but also developed their own cultural community and preserved their identity. There were established English schools, opened English bookstores, started English newspaper agencies, practiced their religions and kept their recreations from their home country. Valparaiso is an example of huge British cultural influence in Chile because of its geographical location and economic activities. In 1895, British population in Valparaiso had reached 1974 out of 10, 302 foreigners.[45] There were cricket clubs, boat clubs and English amateur theatrical clubs.[46] Even though Chile is a mainly Catholic country with strict religion laws back in the early 19th Century, Valparaiso has not shown that much of Catholic influence. Chilean government gave exceptions to Valparaiso because it was an international city with large numbers of foreign merchants and families settling in the city. Under Bernardo O’Higgins’s presidency, he allowed Protestant cemetery in Valparaiso. Thus, the Dissidents’ Cemetery was opened in 1825.[47] The St. Paul’s Anglican Church showed the solidarity within British community. The project was built by William Henry Lloyd in 1857 so that British residents in the city could practice their religion. The architecture style adopted Gothic style like “it was in Early English style, with a lofty hammer-beam roof” according to Lloyd’s journal in 1900.[48] British immigrants have preserved their cultural identity in Chile while adapting to a new life.

Conclusion

British-Chilean relation was developed under mutual needs in the 19th Century when the world was transforming to a global market after the First Industrial Revolution. For Chile, Great Britain was a good ally economically because they provided their expertise in trades, industry and infrastructures. Chile was also a country with rich primary materials such as nitrate, gold, silver and copper, which made them an important partner to trade with. Based on this bilateral trade relations, coastal cities like Valparaiso became the commerce center with loads of imported and exported goods. To improve efficiency, Chile built railroad systems over the course of a century to expand their transportation network so that mining materials could be easily shipped from remote towns to coastal cities. British engineers like William Henry Lloyd had contributed to many railroad projects when Chile was lack of technology and human capitals.

Immigration was growing during the 19th Century, as many merchants, their partners and families arrived in Chile continuously under Chilean government support. British immigrants could start their transnational and local businesses easily with government benefits. Valparaiso and Magellan regions became popular places for British immigrants. They had established their local cultural communities while preserving their cultural identity. Economic opportunities led to the waves of British immigration.

British presence in Chile showed both progress and modernization. In terms of trade, Great Britain was the majority importer and exporter to Chile. Moreover, British merchants and companies were the ultimate beneficiaries from this trade relation after they set up local agencies in Chile. Despite Chile had transformed from a colonial society after breaking ties with the Spanish crown, they still continued the colonial economy in their national development by exporting their primary materials under a monopolized model. Their wealth was sent to overseas more instead of keeping it to themselves. In a few words, Chile still continued neocolonial structure with Great Britain. On the other hand, British infrastructures and immigration had helped Chile progress significantly in a century. Railroad projects could not be even possible without British engineers and capitals. British immigrants also brought diversity and introduced their knowledge in specific areas such as sheep ranching, international commerce and technological companies.

[1] Michelle Prain Brice, “El Legado William Henry Lloyd Neogótico y Modernización en Valparaíso” in El Neogótico en la Arquitectura Americana: Historia, restauración, reinterpretaciones y reflexiones, ed. Martín M. Checa-Artasu & Olimpia Niglio (Ermes. Servizi: 2016): 145-156.

[2] “Británicos en Chile”, Memoria Chilena, Biblioteca Nacional de Chile, accessed April 16, http://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/602/w3-article-3316.html

[3] Jamie Ross, “Inmigración británica en Chile”, Geni, August 17 2011, accessed July 8 2019, https://www.geni.com/projects/Brit%25C3%25A1nicos-en-Chile-British-in-Chile/3243

[4] Eugénio, Vargas García, “¿Imperio informal? La política británica hacia América Latina en el siglo XIX.” Foro Internacional XLVI, no. 2 (April-June, 2006): 354.

[5] Michelle Prain Brice, “El Legado William Henry Lloyd Neogótico y Modernización en Valparaíso” in El Neogótico en la Arquitectura Americana: Historia, restauración, reinterpretaciones y reflexiones, ed. Martín M. Checa-Artasu & Olimpia Niglio (Ermes. Servizi: 2016): 145-156.

[6] Matthew White, “The industrial Revolution”, Georgian Britain, British Library, Oct 14 2009, accessed February 26, https://www.bl.uk/georgian-britain/articles/the-industrial-revolution.

[7] John Mayo, “Britain and Chile, 1851-1886: Anatomy of a Relationship”, Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 23, no. 1 (1981): 96.

[8] Ibid 100.

[9] Simon Collier & William F Sater, History of Chile, 1808-2002, Cambridge, UK (Cambridge University Press, 2004), 45.

[10] Jay Kinsburner, “The Political Influence of the British Merchants Resident in Chile during the O’Higgins Administration, 1817-1823”, The Americas 27, no. 1 (1970): 28.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ariel Batres Villagrán, “Antonio José de Irisarri, a 143 años de su muerte”, Monografías.com, June 10 2011, accessed April 19 2020, https://www.monografias.com/trabajos87/antonio-jose-irisarri-143-anos-su-muerte/antonio-jose-irisarri-143-anos-su-muerte.shtml

[13] Simon Collier & William F Sater, History of Chile, 1808-2002, Cambridge, UK (Cambridge University Press), 44.

[14] L.C. Derrick-Jahu, “The Anglo-Chilean Community”, Biblioteca Natcional de Chile collection, (n.d): 164-165.

[15] L.C. Derrick-Jahu, “The Anglo-Chilean Community”, Biblioteca Natcional de Chile collection, (n.d): 165.

[16] Juan Ricardo Couyoumdjian, “El Alto Comercio de Valparaíso y Las Grandes Casas Extranjeras, 1880-1930. Una Aproximación”, Historia (Santiago) no.33, 2000, http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-71942000003300002.

[17] Ibid 165.

[18] Juan Ricardo Couyoumdjian, “El Alto Comercio de Valparaíso y Las Grandes Casas Extranjeras, 1880-1930. Una Aproximación”, Historia (Santiago) no.33, 2000, http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-71942000003300002.

[19] Samuel J., Martland, “Trade, Progress, and Patriotism: Defining Valparaíso, Chile, 1818-1875”, Journal of Urban History 35, no.1 (2008): 59.

[20] Rory M. Miller, “The Collapse of the Anglo-South American Bank”, The Business History Conference, 2017, accessed May 1 2020, https://thebhc.org/collapse-anglo-south-american-bank

[21] ‘Immigration”, Anglophone Chile Project, accessed May 1 2020, http://anglophonechile.org/brits-in-chile/cultural-history/immigration/.

[22] Baldomero Estrada Turro, “Desarollo Empresarial Urbano e Inmigración Euorpea: Españoles en Valparaíso, 1880-1940”, Memoria Para Optar al Grado de Doctor, Universidad Complutense de Madrid :18.

[23] Jay Kinsburner, “The Political Influence of the British Merchants Resident in Chile during the O’Higgins Administration, 1817-1823”, The Americas 27, no. 1 (1970): 27.

[24] Baldomero Estrada Turro, “Desarollo Empresarial Urbano e Inmigración Euorpea: Españoles en Valparaíso, 1880-1940”, Memoria Para Optar al Grado de Doctor, Universidad Complutense de Madrid: 63.

[25] Ibid 20.

[26] John Mayo, “Britain and Chile, 1851-1866: Anatomy of a relationship”, Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 23, no.1 (1981): 101.

[27] “Británicos en Chile”, Memoria Chilena, Biblioteca Nacional de Chile, accessed April 16, http://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/602/w3-article-3316.html

[28] Guillermo Guajardo Soto, Tecnología, estado y ferrocarriles en Chile: 1850-1950, (Mexico, Fundación de los ferrocarriles españoles, 2007), 39.

[29] “La Constitución de 1833”, Memoria Chilena, Biblioteca Nacional de Chile, accessed April 19 2020, http://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/602/w3-article-3506.html

[30] “Los ciclos mineros del cobre y la plata (1820-1880)”, Memoria Chilena, Biblioteca Nacional de Chile, accessed April 19 2020, http://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/602/w3-article-727.html#presentacion

[31] Michelle Prain Brice, “El Legado de William Henry Lloyd: Negótico y Modernización en Valparaíso”, in El Neogótico en la Arquitectura Americana: Historia, restauración, reinterpretaciones y reflexiones, ed. Martín M. Checa-Artasu & Olimpia Niglio (Ermes. Servizi: 2016), 148.

[32] “Railways for Chile”, Valparaiso and West Coast Mail, Anglophone Chile Project, August 19 1871, accessed April 19 2020, http://anglophonechile.org/newsarchive/files/original/e361d7b0be536d9b7127e4571c96c32f.pdf

[33] Michelle Prain Brice, “El Legado de William Henry Lloyd: Negótico y Modernización en Valparaíso”, in El Neogótico en la Arquitectura Americana: Historia, restauración, reinterpretaciones y reflexiones, ed. Martín M. Checa-Artasu & Olimpia Niglio (Ermes. Servizi: 2016): 150.

[34] Guillermo Guajardo Soto, Tecnología, estado y ferrocarriles en Chile: 1850-1950, (Mexico, Fundación de los ferrocarriles españoles, 2007), 11.

[35] Michelle Prain Brice, “El Legado de William Henry Lloyd: Negótico y Modernización en Valparaíso”, in El Neogótico en la Arquitectura Americana: Historia, restauración, reinterpretaciones y reflexiones, ed. Martín M. Checa-Artasu & Olimpia Niglio (Ermes. Servizi: 2016): 148-149.

[36] Ibid 146.

[37] Ibid 150.

[38] Ibid 149.

[39] Ibid 150.

[40] Jay Kinsburner, “The Political Influence of the British Merchants Resident in Chile during the O’Higgins Administration, 1817-1823”, The Americas 27, no. 1 (1970): 32.

[41] F Vargas Fontecilla, “Decree of the Chilean Government Encouraging Emigration to the Colony of Magallanes, on the Straits of Magellan”(Department of The Interior, Biblioteca Nacional de Chile collection, Santiago, December 2, 1867, 2-3.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Mateo Martinic Beros, “La Participación de Capitales Británicos en El Desarrollo Económico del Territorio de Magallanes (1880-1920)”, Historia (Santiago) 35 (2002), https://scielo.conicyt.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0717-71942002003500011

[44] Ibid.

[45] Baldomero Estrada Turro, “Desarollo Empresarial Urbano e Inmigración Euorpea: Españoles en Valparaíso, 1880-1940”, Memoria Para Optar al Grado de Doctor, Universidad Complutense de Madrid: 60.

[46] Francisco Ignacio Rickard, A Mining Journey Across the Great Andes, (London, Smith, Elder & Co., 1863), 12.

[47] Samuel J., Martland, “Trade, Progress, and Patriotism: Defining Valparaíso, Chile, 1818-1875”, Journal of Urban History 35, no.1 (2008): 59.

[48] Michelle Prain Brice, “El Legado de William Henry Lloyd: Negótico y Modernización en Valparaíso”, in El Neogótico en la Arquitectura Americana: Historia, restauración, reinterpretaciones y reflexiones, ed. Martín M. Checa-Artasu & Olimpia Niglio (Ermes. Servizi: 2016): 153.