Introduction to Sor Juana Inés de La Cruz’s Life

In Colonial Latin America, patriarchal society was the norm. Males were viewed as superiors over females, and women were expected to maintain primarily domestic roles in the household. In fact, this biased gender role was an aspect of the social hierarchy even during the post-Colonial era in Latin America. While many women abided by this gender role, a particular woman went against it, becoming a controversial feminist during the 1600s. Even significant today, this woman is known as Sor Juana Inés de La Cruz. As a self-taught scholar, nun, poet, playwright, and composer, Cruz demonstrated all the unique elements of a woman present in a patriarchal society. While Cruz was able to rise up and challenge the gender roles of her time by publishing controversial works, there were major effects of her expressing her voice as she faced gender discrimination and succumbed to hegemony at the end of her career. However, her legacy as the pioneering feminist of Latin America remains important in the modern day as she continues to inspire feminist movements.

Cruz was born out of wedlock in 1651 near Mexico City, Mexico, demonstrating the fact that even the beginning of her life was out of the ordinary. During her early years, she was an eager reader and even wrote her first poem at the young age of eight. Due to her eagerness to learn about the world, she had the desire to disguise herself as a man so she could go to a university, but her family would not allow her to do so. However, this did not stop her from becoming a self-taught scholar as she studied privately. Her knowledge sparked the interest of Antonio Sebastián de Toldeo, marquis de Mancera. Mancera then invited her to stand before a panel that was composed of scholars to test her intelligence. She was found to have a vast amount of knowledge and skills. Around this time, Cruz had also declared that she had no interest in marriage, so she decided to become a nun. Cruz decided to join the covenant as she would be able to continue her studies without interruption, describing it as “the least unsuitable and the most honorable” way of life. By obtaining vast knowledge and departing from the female norm, this sparked public interest in Cruz throughout Mexico, marking the beginning of the development of Cruz as a controversial figure.

Cruz’s Controversial Views Expressed in Her Plays and Poems

Cruz devoted much of her life to publishing artistic works that challenged the patriarchal gender role that she, and many other women, were experiencing. By publishing works such as plays, poems, letters, and musical works, she was able to challenge radical feminist views. One of her significant works, The Trials of a Household, is a play in which she voices her views against the injustices that women face. In this play, Cruz portrays Doña Leonor, a fictional character who departs from the female norm by self-depicting herself as a brilliant scholar. Leonor has no choice in her life, not even having the ability to choose her husband. For this reason, she departs the female norm by declaring her knowledge and describes the man she loves in a way that men would describe women. This represents an analogy to Cruz herself in that she rejected marriage, showing one way how she departed from the female norm. In addition, this play signifies how Cruz did not want to portray the domestic role of women, and how she defended this role in regard to other women. By writing Trials of a Household, Cruz upheld the bravery to speak up against injustices in ways that, at the time, was completely unheard of.

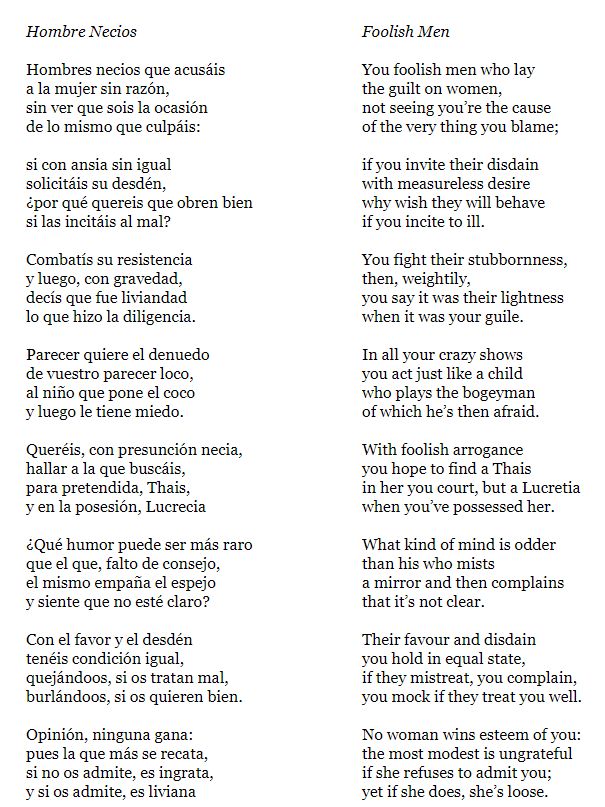

Considered the pioneering feminist poet of Latin America, Cruz also expressed her radical views through poems. Written in the 1680s, Cruz’s Foolish Men is one of her famous poems that expresses her disappointment in the hypocrisy of the relations between men and women. Her poem begins by saying, “You foolish men who lay the guilt on women, not seeing you’re the cause of the very thing you blame.” This line is saying that men blame women for the things that the men are guilty of, without realizing it, making the men fools. After this line, the poem goes on to explain how men view women and highlights the fact that many of these perspectives are often wrong. In the fifth line, Cruz states a strong metaphor: “With foolish arrogance you hope to find a Thais in her you court, but a Lucretia when you have possessed her.” Thais was a sex worker who accompanied Alexander the Great, while Lucretia was a Roman noblewoman who had committed suicide after she was raped to preserve her family’s honor. By mentioning this metaphor, Cruz is accusing men of wanting a double standard. Men disrespected both kinds of women but wanted them both at the same time, demonstrating their contradictory views of women. Like many of her feminist views, this criticism of males was extremely radical for her time. Despite the consequences of her actions, Cruz was not willing to give up until her views were heard loud and clear.

The Tense Relationship Between Cruz and the Catholic Church

As a nun, religion was an important aspect of Cruz’s life. However, by choosing to express her radical feminist views, this challenged the relationship between her and the Catholic Church. The church feared her influence on other women, afraid that many would follow in her footsteps and would result in damage of the church’s social hierarchy. Due to this fear, the Church sought to silence her and any women that appeared to be influenced by Cruz. This grew the attention of Manuel Fernández, Bishop of Puebla, who wrote her a letter signed as “Sor Filotea.” In this letter, he explained that women should keep silent. He claimed that while he appreciated Cruz’s work, he claimed that it was a “waste of time.” Instead of publishing controversial works, he believed that she should use her talents instead for spiritual matters, especially since she devoted her life as a nun. In response, Cruz addressed the famous letter as Respuesta a Sor Filotea. Despite his critical words, Cruz was not hesitant to defend the historical and spiritual rights of women to study. Defending this type of statement was unheard of as many believed that it was “unnatural” for a woman to pursue these interests. Cruz also acknowledged the fact that while she often tried to focus on religion rather than her studies, it was impossible to ignore her eagerness to learn. While religion was a defining aspect of Cruz’s life, it shows courage that she was able to challenge a woman’s right to learn at the expense of harming the relationship between her and the Catholic Church.

By defending the spiritual rights of women to study, Cruz was attempting to expand the range of acceptable activity for women in the church. To do so, she pushed against the limitations in freedom of speech for religious women, demonstrating the ideas of heterodoxy and paradox to Cruz’s personal understanding of her Catholic faith. According to scholar Alejandro Soriando Vallés, he views Cruz’s faith as “framed in one of these two ‘sides’: anti-establishment criticism, which raises the confrontation of the nun with the establishment, and the Catholic one, supportive of the notion of her fidelity to orthodoxy.” This is significant to note in that it offers a powerful example of the type of negotiation that religious women had to undergo to attempt to get the Catholic Church to understand their voice after continuously silencing them. These contrary ideas showcase the clash between her obligations as a nun and her desire to continue her studies, a major difficulty of Cruz’s life, as discussed prior. While her efforts ultimately failed, her voice prevailed centuries later.

Cruz Often Faced Gender Discrimination

In addition to her interests in mathematics, natural sciences, visual arts and rhetoric, Cruz had a desire to learn about music. Living in the Baroque period, she devoted a portion of her studies to the theory of instrumental tuning. She even wrote a musical treatise, titled El Caracol, which was unfortunately lost. The title suggests that Cruz favored the Pythagorean tuning system. The Pythagorean tuning system favors mathematical perfection over musical function. This shows how Cruz’s interest in mathematics intertwined with her interest in music. However, later scholars challenged this view, claiming that music was more related to rhetoric than mathematics. Furthermore, it is important to note how other scholars related to her musical works. A later scholar, known as Electa Arenal, critically analyzed her musical works. In one of his analyses, he claimed that traditional scores were “too discordant and disconcerting to the ears of (female) intelligence. ” This statement is directly insulting Cruz by downplaying her intelligence as a woman scholar. These instances where scholars criticized her understanding of music, as well as her musical works, represent the gender discrimination that Cruz had faced. During her time, it was hard to believe that a woman was capable of becoming an intellectual, especially by having the ability to understand or compose music. However, this gender discrimination does not take away from the fact that Cruz portrayed a truly unique role of women of her time, even though she was later utterly disrespected.

Unfortunate Ending of Cruz’s Life and Career

Unfortunately, the end of Cruz’s career turned to the worst. Feeling pressure from the Catholic Church, she ultimately succumbed to hegemony, a type of social control in which a ruling class dominates others ideologically. She could no longer defy the pressure she was facing, so she consented and sold all of her works, ending her career as a writer. The rest of her life she spent in atonement for the sin of curiosity. In addition, she felt sorry for abandoning her religious duties, claiming she was the “worst of all women,” and spent the remainder of her life in upholding these responsibilities. This weakened her spirit as she was then suppressed of intellectual freedom and felt abandoned by the people in her life. A few years later, in 1695, Cruz was caring for her fellow nuns during a plague epidemic. As a result, Cruz was exposed to the plague and fell victim to it. Cruz spent the last part of her life caring for others, costing her own life.

Cruz’s Impact

Despite the unfortunate ending of Cruz’s life and career, her story and accomplishments have lived on. During the 20th century, Cruz was recognized as the first published feminist of the New World due to the rising interest in feminism. In addition, she has been recognized as Colonial Latin America’s first great poet and the last great poet of the Spanish Baroque. Cruz became a role model to women readers during the 20th century as they were inspired by her writings. They viewed her as an “icon of female intellectual independence.” One of these women was Rosario Castellanos, a Mexican feminist writer and scholar. In 1973, Castellanos wrote Mujer que sabe latín, which translates to Woman That Knows Latin, which is one of her famous feminist works. In this work, she lists examples of pre-twentieth century feminist women who broke traditional roles and “attained their authentic image and… chose themselves and preferred themselves over all others.” Castellanos listed Cruz at the top of the list, viewing her legacy as a legend. This represents the significance of Cruz centuries after her life. While Cruz expressed views ahead of her time, feminists have remembered her many years later, expressing the same views. If Cruz would have lived during the time of these feminist movements, the end of her career likely would have had a different result.

Conclusion

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, the first feminist of Latin America, held a unique role of her time. From her childhood until the end of her career, she had a strong desire to learn, which was a unique characteristic of women at the time. She was not afraid to express her views, though it was unheard of at the time to do so. Through her various works, it is clear that Cruz wanted her voice to be heard by women suffering in a patriarchal society. As a nun, expressing her radical views hurt her relationship with the Catholic Church. However, as a brave and strong woman, she did not back down until the last few years of her life. Today, she inspires many and stands as a national icon of Mexican identity. Cruz may not have been successful in her lifetime, but her legacy as a feminist remains important to this day.

References:

Chasteen, John Charles (2016). Born in Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America (4th ed.).W.W. Norton & Company. North Carolina: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Cortés-Vélez, Dinorah (2019). “Faith and Dissidence in Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.” In A Companion to World Literature, K. Seigneurie (Ed). doi:10.1002/9781118635193.ctwl0117

De la Cruz, S.J.I., Arenal, E., Powell, A., & B06 (2011). The Answer/La Respuesta. (Second Critical Edition ed.). New York: The Feminist Press. muse.jhu.edu/book/14516. Accessed 29 Feb. 2020.

Finley, Sarah. Hearing Voices: Aurality and New Spanish Sound Culture in Sor Juana Inés De La Cruz. University of Nebraska Press, 2019. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvb1hr9g. Accessed 4 Abr. 2020.

Long, Pamela H. (1990). El caracol: Music in the works of Sor Juana Inés de La Cruz. Tulane University. New Orleans: Tulane University. https://digitallibrary.tulane.edu/islandora/object/tulane%3A27540. Accessed 17 Abr. 2020.

Merrim, Stephanie. (2020). “Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Mexican Poet and Scholar.” Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sor-Juana-Ines-de-la-Cruz. Accessed 17 Abr. 2020.

Seminar on Feminism & Culture in Latin America. Women, Culture, and Politics in Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft7c600832. Accessed 17 Abr. 2020.

(2018). “Teaching Women’s History: Sor Juana Inés de La Cruz, Feminist Poet of New Spain.” Women at the Center. New York: New-York Historical Society Museum and Library. http://womenatthecenter.nyhistory.org/juana-ines-de-la-cruz- feminist-poet-of-new-spain/. Accessed 17 Abr. 2020.