Jamaica originally began as a military garrison under Cromwell’s Western Design in 1655, which brought English soldiers to the island.[1] Due to the harsh environment of the Caribbean, the island was, “a dismal failure as a military garrison [however], Jamaica achieved success when converted in 1661 into a royal colony.”[2] This began European expansion on the island which would result in the structures we see during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Once established as a colony of Britain, European indentured servants were used for labor but quickly replaced by African slaves. This period of slavery in Jamaica ended in 1834. Within Jamaica, constructions of race and class established a social hierarchy that in many ways reflected the social structures of many other Latin American countries. The diversity of the population in Jamaica by the nineteenth century can be narrowed to three non-Native groupings, which this paper will discuss: Europeans, Africans, and South Asians. This is significant because it provides a new framework for understanding Latin America in the nineteenth century. This approach is useful when trying to place close analytics of a country into the larger context in understanding the area.

Headley Bernard analyses the relationship between whites and blacks in Jamaica. His work, “attempts to locate and define racial groups in terms of their relationship to the social structure, and traces of the historical development of this relationship.”[3] This article is oversimplified in analyzing only two groups in Jamaica, however, in doing so, he defines an essential aspect of black and white race relations and provides the basic framework for understanding the social hierarchy in Jamaica. His framework applies to many countries in Latin America. With European powers exercising hegemony over the region and engaging in the Transatlantic Slave Trade, this power dynamic between Africans and European was established.

Bernard uses the work of many other historians and sociologists in his work in order to bolster his own framework. He uses Van den Berge’s claim that, “race relations [are]… perceived physical differences”[4] and that, “’races’ do not exist unless groups are defined as such on the basis of differences that are socially recognizable.”[5] This establishes the basic principle of Bernard’s claim that the, “underlying factor in competitive race relations is the unequal allocation of scarce resources.”[6] The unequal distribution of resources based upon perceived physical differences is how whites all across Latin America established systems of control and power over Africans and any other non-white groups. Bernard furthers his point by quoting Kinloch and looking at their framework. Kinloch states, “that as economic development takes place, racially defined minorities will begin to reject the negative definitions imposed on them by those in power.”[7] Kinloch’s view is too simplified. Anyone subject to unjust treatment under this theory will automatically revolt. While this occurred in Haiti, it did not in many other Latin American countries. Bernard addresses this in the context of Jamaica. Unlike van Berge, Kinloch serves as a framework to disprove. Bernard takes Kinloch’s theory further with a Marxist aspect. He writes that the, “underlying constant is conflict based on access to the means of production.”[8] This holds true both in Jamaica as well as the rest of the world where inequality between social groups exist. Those in power are those with access and control of resources and therefore distribution. It is not enough to accept Kinloch’s theory, but it needs to be expanded it with a Marxist framework. These relations in Jamaica represent black and white relations in most of Latin America.

The last theorist Bernard uses to prove his framework is Berry and Tischler (1978). They argue that “although conflict is not inevitable, it is often quite often a universal accompaniment to interracial contact. Biological mixture is another.”[9] As in Chasteen’s book Born in Blood and Fire, a distinct feature of Jamaica, as well as Latin America is the racial mixture of people. Bernard’s work analyzes the racial distinctions between Africans and whites but then also acknowledges this racial mixture that became important when studying race relations in Jamaica. These relations were not simply, black, white, and natives; rather they were to some extent fluid with the birth of children between these groups. This mixture in no way minimizes the distinct categories of difference. The treatment of groups seen as non-white were brutal during the colonial slave period. The race relations seen in Jamaica during this time demonstrate the social relations seen across many countries in Latin America.

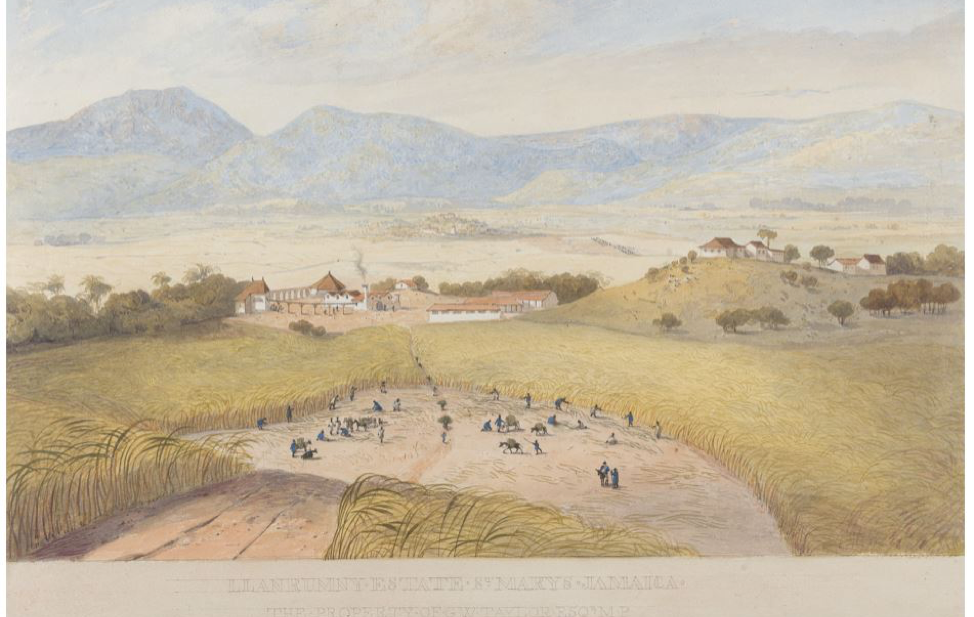

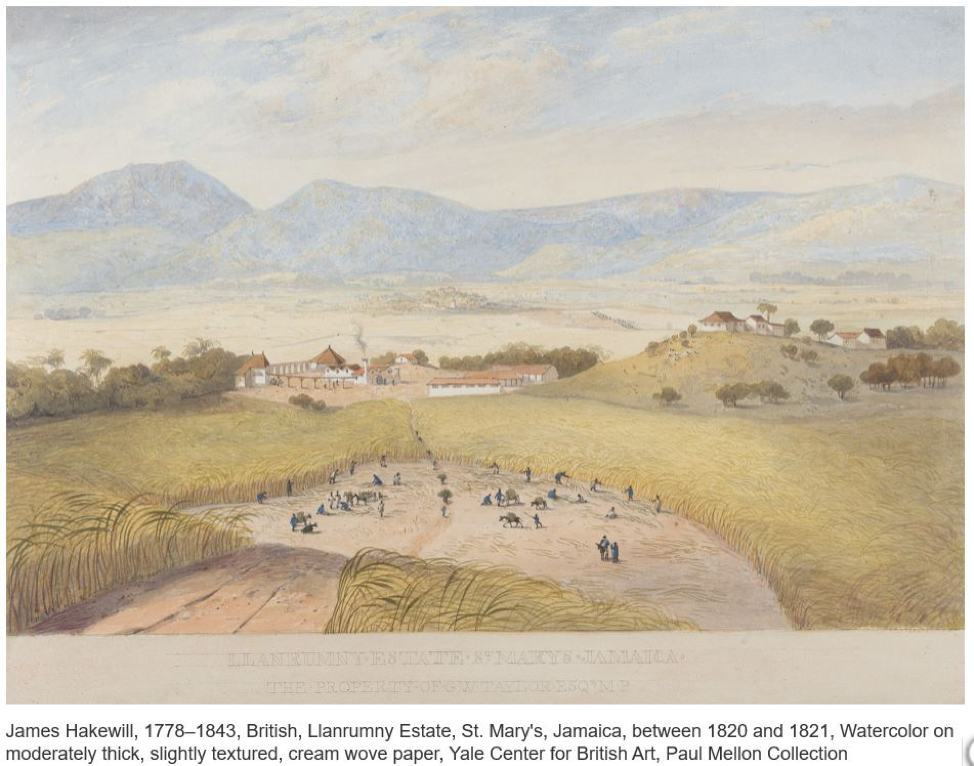

The painting by James Hakwill of the Llanrumny Estate in St. Mary’s, Jamaica exemplifies black white relations. As seen in the foreground, what can be assumed to be African slaves, are working in the fields while behind the fields is the plantation where the masters and slaves would have lived. We can also see that the buildings are in two sections, a group of buildings for the slaves and on the other side a group of buildings for the slave owners. This sharp distinction was not simply social, but it was also physical. Physical characteristics and physical distance. The Europeans worked to establish themselves apart from all others in every way they could. Through the use of “science” to prove superiority, controlling the power structures, and many other ways, they ensured that they were in control at all times.

In the background of James Hakewill’s painting are mountains. These mountains hold a deeper meaning than simply being part of the landscape. One group that is often referenced but not a part of the larger literature are the Maroon communities across Latin America. These communities are, “peoples of the African Diaspora who escaped from enslavement and lived independently of plantation societies in the Americas.”[10] In Jamaica Maroon communities lived in the mountains. The reason these groups are sometimes not in this narrative is because they lived autonomously in the hills of Jamaica and other countries away from plantations and established society. They belong in this history because they are a part of Jamaica and therefore the social structures. We can understand these groups to be above that of slaves because they are free. Unlike the system of slavery in the United States later in history, Europeans in Jamaica did not hunt down escaped slaves. During the eighteenth century, there was a constant flow of Africans to the Americas. While slave masters did not encourage escaping, they did not actively seek out their lost slaves. It was not easy to escape either. As an island, there weren’t many places left to go and the mountains were hard to get to let alone the Maroons who lived deep in the mountains where it was difficult to traverse to. The existence of Maroon communities did give hope to slaves across the Americas because it was proof that a free autonomous group of Africans did exist and thrived in the mountains.

After Jamaican emancipation in 1834, plantation owners sought new sources of labor. In order to maintain their wealth and crop production, “planters in Jamaica attempted to regain necessary labor by hiring ex-slaves and importing labor from Africa and South Asia.”[11] As the British Empire was expanding, they looked to East Indians to replace the freed slaves that had left their plantation. From, “1844 and 1917, South Asians immigrated to Jamaica from East India Company holdings in Bengal and Madras.”[12] This source of cheap labor added to the cultural and racial diversity of Jamaica. Even though, “the East Indian populations represents a small minority… they are a significant minority”[13] that added to the dynamics between Africans and Europeans. While they did not own land, and therefore the means of production, they were also never slaves. They could not be bought and sold as another person’s possession but were far from modern conceptions of free. This distinction created disputes and tension between Africans and South Asians. Though there are multitude of reasons there was tensions between the two groups, “Verene Shepherd (1988) argues that… [the] conflict… [was] predicated on constructs of ethnicity and race… The planters took advantage of the ensuing antagonism between laborers from South Asia and Africa to retain control over labor.”[14] We see here that in this context, Europeans took advantage of animosity between labor to ensure that they would never rise against the Europeans. The emergence of another racial category, “can add to our understanding of the true depth of diversity in the emergence of social landscapes.”[15] As in Jamaica and many countries in Latin America such as Brazil, Peru, Mexico, Venezuela, and Argentina, the introduction of Asians in these areas forced a shift in categories and who belonged where. It is no question, Europeans fought and, in most cases, succeeded in remaining at the top of the social hierarchy, but the question became, where did the other groups fit in? Who would have the most rights and who would be considered the bottom of the hierarchy?

In the photograph of indentured Indian servants, we can see that the conditions in which South Asians lived were like those of previously enslaved Africans. This further demonstrates the social hierarchy of Jamaica. South Asians entering Jamaica were moved onto plantations to replace the African labor force, but the treatment they received by Europeans did not change much at all from the treatment Africans got. With the introduction of indentured servitude, or a new form of slavery, Africans found that they had been replaced to some extent and therefore lost all bargaining power they had in trying to establish wages and create homes for themselves. The tensions between Africans and South Asians stemmed ultimately from power dynamics.

In conclusion, the social and racial hierarchies of Jamaica were products of power dynamics. With European dominating over African and South Asian labor in Jamaica since the seventeenth century, systems of control over non-white groups were established in Jamaica. Today, the racial mixture in Jamaica is a product of colonization because all three races have contributed to the diversity seen in the country. The history of Jamaica’s racial and social hierarchies can be used to analyze many countries in Latin America. The introduction of European’s seeking control of resources and establishing cash crops is a common theme in Latin American countries. In addition, the use of African slaves and then South Asians as a means to replace labor after emancipation is not solely Jamaica’s history, rather this very broad overview of history can be applied to countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela, and many others. While close examinations of individual Latin America countries have been done, this paper has taken a broad overview of Latin America to look these structures. By applying Jamaica’s broader history to Latin America, a richer overview of the South America and the Caribbean can be studied.

[1] Trevor Burnard. “European Migration to Jamaica, 1655-1780.” The William and Mary Quarterly 53, no. 4 (1996): p. 771.

[2] Ibid., 771.

[3] Bernard D. Headley. “Toward a Cyclical Theory of Race Relations in Jamaica.” Journal of Black Studies 15, no. 2 (1984): 208.

[4] Ibid., 208.

[5] Ibid., 208.

[6] Ibid., 221.

[7] Ibid., 212.

[8] Bernard D. Headley. “Toward a Cyclical Theory of Race Relations in Jamaica,” 221.

[10] Weik, Terry. “The Archaeology of Maroon Societies in the Americas: Resistance, Cultural Continuity, and Transformation in the African Diaspora.” Historical Archaeology 31, no. 2 (1997): 81.

[11] Douglas Armstrong, and Mark W. Hauser. “An East Indian Laborers’ Household in Nineteenth-Century Jamaica: A Case for Understanding Cultural Diversity through Space, Chronology, and Material Analysis.” Historical Archaeology 38, no. 2 (2004): 11.

[13] Ibid., 10.

[14] Ibid., 11.

[15] Douglas Armstrong, and Mark W. Hauser. “An East Indian Laborers’ Household in Nineteenth-Century Jamaica: A Case for Understanding Cultural Diversity through Space, Chronology, and Material Analysis,” 10.